Finding the Sound of LEOPOLDSTADT

Adam Cork is behind the Sound Design and Original Music of Broadway's Leopoldstadt.

|

|

Just close your eyes at the Longacre Theatre and you will be transported from the heart of New York City to 20th century Vienna. That is thanks to the maticuous work of Adam Cork, who acted as Sound Designer and created original music for Tom Stoppard's Leopoldstadt. Cork is giving us a glimpse into his creative process of bringing the sounds of Austria to life on Broadway. Read his full essay below!

Learn more about the designs of Leopoldstadt here!

The themes of 'Leopoldstadt', its setting, the epic arc of the history it delineates from 1899 to 1955, together with the events and relationships so movingly brought to life by Tom Stoppard's writing and Patrick Marber's direction, provided a rich and well nigh bottomless reservoir of ideas and feelings which helped me bring to life the sound design and original composition for this production.

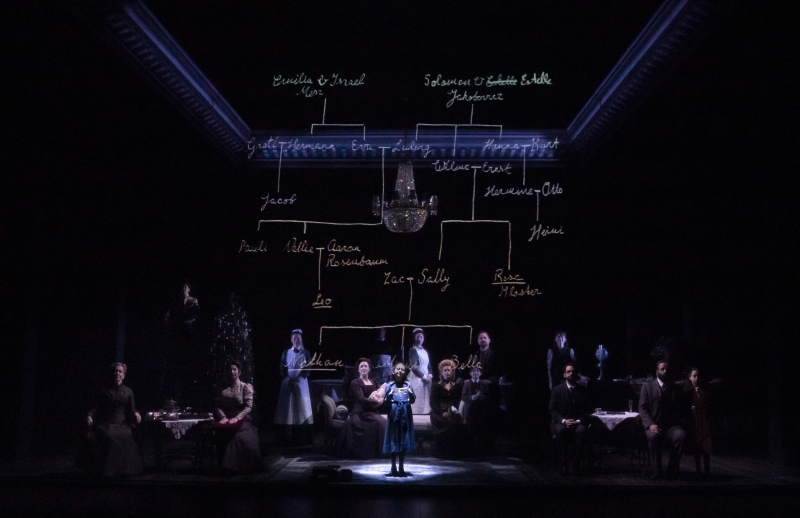

The play begins at Christmastime in 1899 Vienna, and questions of assimilation and identity are in the air from the outset. Prosperous Hermann extols the virtues of fitting in, despite not being accepted everywhere in society due to his Jewish family background. His brother-in- law Ludwig puts the opposite case - assimilation as a strategy is doomed to failure.

These issues were live for two giants of Viennese music, Gustav Mahler and Arnold Schoenberg, both Jewish, both (like Hermann) converts to Christianity. The latter eventually fled Austria with the rise of the Nazis. His sense of identity in both music and life grew closer to his Jewish roots as he grew older, but we begin the play with an excerpt from his early 'Verklarte Nacht', written in the late Romantic Austro-German style that makes it 'assimilated', yet also full of expectation, mystery, a brooding uncertainty about the future which is neither quite dread or excitement, anxiety or optimism, but contains an almost prophetic sense of trembling on the edge of a precipice at the turn of the 20th century. Mahler, also Jewish, died much earlier and seems to have followed the 'assimilated' path throughout his adult life, however his music is replete with 'unassimilated' moments within the received styles that gave him his material.

Although we don't use any of his music in the production, this particular notion is the inspiration for my own 'Leopoldstadt Waltz.' I took the Strauss waltz style and gave it a Mahlerian turn - places where the melodic decoration - ornament in Strauss - is leant upon a little more heavily, to the point where it takes on a more structural harmonic meaning - a feeling of being lost, but with pleasure as well as sadness. This provides a flavor which underscores 1899, lends an invisible solidity to the Viennese setting, a certain Christmassy cosiness in complementing the sense of family warmth, but is also designed to support the aching nostalgia when it returns at later moments in the play.

That sense of being lost, of being perpetually in transit, never quite at home, also feeds into the musical language which carries us through the scenes in the 1899/1900 act. I chose a tempo suggestive of being on a journey, but perhaps a journey of adventure and potential in this initial period of the play, which combines with a hint of the Schoenbergian abyss as we move from scene to scene, whilst at the same time horses trot and gallop through the Viennese streets, conjuring a literal sense of travel, with an urgency ranging from the genteel to the passionate.

Carving out a music and sound design language for 1899/1900 was just the first challenge, as 'Leopoldstadt' is like four plays in one evening. There's also the excitement of collaborating with other departments to ensure our individual efforts all work well together. Exchanging material with video designer Isaac Madge, aiming together towards an audio/visual complicity. Trying out different versions of the music together with choreographer E.J. Boyle. Knowing the information lighting designer Neil Austin will need as he shapes lighting cues alongside the music and sound with sensitivity and flair, while Patrick Marber directs all departments towards his vision of the whole.

There's also the practical challenge of ensuring the words can be heard. Stage microphones can deliver a certain character, as they capture some of the acoustic around a voice as well as the voice itself, which I've always found has the potential to contribute to a sense of reality and solidity - the actual space is enhanced, bringing the set to aural life at the same time as supporting the voice. Whereas radio (body-worn) microphones by contrast capture the close-up sound of the voice and (ideally) nothing more. This means the potential for greater clarity but on a practical level it's a bigger challenge for the sound mixer (every line means several quick fader-movements), and on an aesthetic level it can impart more sense of artifice if the enhancement is consciously noticeable for an audience - and an artifice which points towards modern technology is not helpful in a historical piece.

Here we have a large cast, mixed adult and child voices, extended sequences where we hear very short successive lines from multiple characters, plus a period setting, so the choice is not an obvious or easy one. In this instance we opted to use radio microphones in order to help communicate the play as clearly as possible. I'm pleased with the natural quality of the final vocal sound and in this I was blessed also with the input of my co-Associate Ed Chapman and my co- Associate-and-sound-mixer-in-chief Chris Cronin.

Then there's the task of helping the production move from era to era. To aid the movement from 1900 to 1924 we have a video sequence comprised of silent film footage from the period, to which I add a soundtrack of voices and effects 'as if' captured at the time, together with energetic Klezmer music. I decided to employ a counter-intuitive sound design strategy to take the quality from earlier/richer to later/cruder. My guiding idea was that the reality of 1900 is rich and vivid, whereas the reality reproduced by the audio and visual technology of 1924 - 'modern' but still in its infancy - is crude. I treat the music so that over the course of its development it takes a slow path from the clean, transparent, full-range sound to a much thinner, flatter image, marred by artefacts such as gramophone dust and scratches, the scars of the early recording media. This then segues into 1920s jazz on the actual gramophone within the stage setting, to which Hermine is rehearsing her Charleston dance.

For the next transition, to 1938, the history itself is hugely suggestive from a sound design point of view. Tom Stoppard asks for 'bombers' to begin with, referencing the first moments of Hitler's annexation of Austria. This was the starting point for me to construct a sound montage representing the overwhelming power and unity of the Nazi military machine on the one hand, and the frightening chaos erupting into the life of our protagonist-family on the other. I continue to underscore the whole of the 1938 scene with a combination of literal sound design suggestive of the occupying forces, as well as more abstracted elements which are shaped to support the ever-present sense of dread which ebbs and flows through the scene and culminates in the eviction of the family from their home.

In the transition which follows I set out to represent the ensuing history initially with a literal sense of destruction - suggestive sounds of smashing glass and militia-mobilisations - which then spirals into a more abstract 'composed' sound design, a shriek of total destruction and total horror as the cataclysmic events of the war unfold.

A virtuosic piece of period Klezmer by Dave Tarras then takes us into 1955 and a post-war modernity many of us recognise (still) as being of 'our' era - an international space whose order depends substantially upon a collusion to ignore parts of history. Although still in Vienna, the presence of American and British characters returned from the diaspora makes us feel we are in Vienna but also somehow simultaneously in London, or New York, and somehow 'now'.

I underscore this scene with quiet traffic, leading with 1950s period sounds, but more subtly in the background I've added a haze of more distant, more modern traffic to support this feeling. Also continuing in the background, and indispensable to the sound world, are the elements which have persisted through all the metamorphoses of period. A nearby church bell has gently tolled through the whole play, and a household clock ticks insistently in every scene from 1899 to 1955, quietly providing a unity which endures through all the variation.

As this scene (and the play) draws towards its conclusion we return in memory to 1899 and finally again to the 'Leopoldstadt Waltz' - a nostalgic longing for lost comfort, lost potential, lost family, lost tribe, but also the unassimilated element which re-construes itself and its surroundings to create a new fusion, its own style, underlining the point that identity is crucial, but sameness allows for no change.

Leopoldstadt is running on Broadway at the Longacre Theatre.

Videos