Review: Ivo van Hove's Alarmingly Charmless WEST SIDE STORY

|

Dear kindly Ivo van Hove,

I often like your work,

But when you stage revivals

Your concepts go berserk.

Your symbolism's clunky,

Your edits are too thick.

West Side Story doesn't need your schtick.

By 1957, the year that director/choreographer Jerome Robbins' original Broadway production of Arthur Laurents (book), Leonard Bernstein (music) and Stephen Sondheim's (lyrics) West Side Story hit town, New York City was deeply feeling the effects of what was referred to at that time as a "white flight."

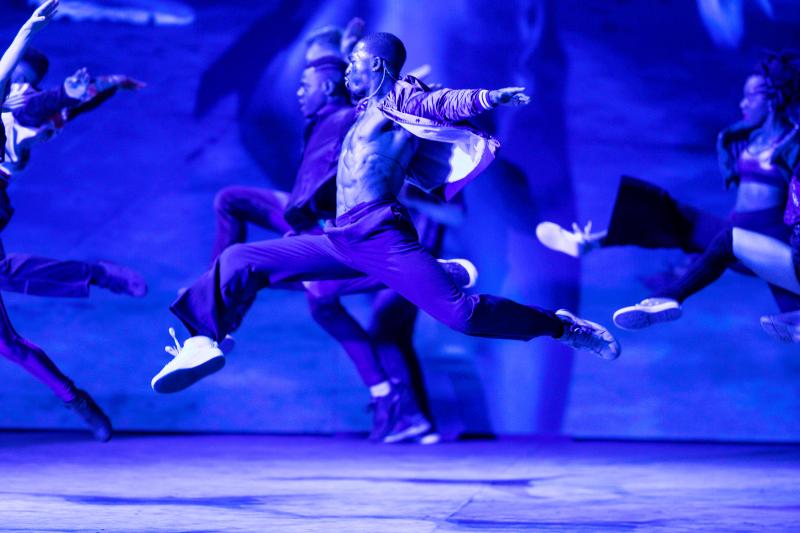

(Photo: Jan Versweyveld)

Aided by the financial benefits of the G.I. Bill, World War II veterans were buying houses in suburban communities made accessible from the roadway system devised by the city's parks and planning commissioner Robert Moses. Corporations and their good jobs joined them, sucking the middle class out of Manhattan.

Meanwhile, the advent of affordable air travel assisted a great migration of Americans from Puerto Rico to move to New York, seeking a better living during a period of economic hardship on their home island. Many of the city's low-income white families, mostly children and grandchildren of European immigrants from the first half of the century, resented these new competitors for jobs who didn't have to go through the naturalization process and targeted them with the same kind of racism their predecessors felt as soon as they arrived.

Fewer prospects for the future fueled an increase in what was called juvenile delinquency, as young people formed violent gangs that terrorized neighborhoods.

These were the news headlines audiences were familiar with when West Side Story premiered, and while Laurents' book contained lines that referred to such issues, it wasn't necessary to overstate what was common knowledge.

Today, such context is largely forgotten, and West Side Story's status as a beloved work of American popular culture comes largely from its tragic romance, paralleling the events of Shakespeare's ROMEO AND JULIET, as Tony, a young New Yorker of Polish descent, and Maria, a recent New Yorker of Puerto Rican descent, fall in love at first sight as the white gang named the Jets and the Puerto Rican gang named the Sharks prepare for an all out rumble to win dominance over their west side turf.

The revival of West Side Story that opened tonight on Broadway is being touted as a 21st Century reinvention of the musical, with director Ivo van Hove discussing in interviews the random senselessness of racism and violence, disregarding how the material so specifically reflected the era it came from.

While new artists should be encouraged to interpret older plays and musicals differently from their predecessors, especially a piece like West Side Story which, through its Broadway revivals and extremely popular film version, has been tied to visuals invented by Robbins (the snapping fingers, the balletic interpretation of violence), there is such a thing as having fresh concepts clash with the material, diluting its effectiveness.

Even before previews began, it became public knowledge that the script would be altered; with the intermission cut and Maria's Act II opening "I Feel Pretty" and the ballet that accompanied the musical prayer for a peaceful world, "Somewhere", both eliminated. Also, the version of the showstopping "America" used on stage, performed solely by the Puerto Rican women, would be replaced by the film version that included the men.

But there's more.

The performance now begins with the Jets and the Sharks walking down to the center of a bare stage, lining up facing the audience and standing still as the music commences.

(Photo: Jan Versweyveld)

And they keep standing still for a long... long time as cameras project huge closeups of their faces onto the dark wall that takes up the entire upstage area. It's a bit like a police lineup, as the characters emotionlessly look straight ahead as the music plays. Others join the line. They also stand still as Bernstein's ravishing symphonic jazz rhythms continue. We see their faces projected in extreme closeup.

And we notice from their hair styles and An D'Huys' costumes, and the numerous tattoos on their faces and arms (eventually we'll see full body tattoos) that these characters live in contemporary times. We'll also see that in the styles of Anne Teresa de Keersmaeker's choreography.

Finally, there's movement. A fight breaks out and the stage is crowded with combat. From this reviewer's seat in orchestra row O, the scene on stage looked dimly lit and unfocused, but extreme closeups were provided by video designer Luke Halls' big, bold projections of the actors, provided by both mounted and hand-held cameras.

When scenes shift to locations inside Doc's drugstore and the dressmaking shop where Maria works, set and lighting designer Jan Versweyveld represents them with small rectangular cutouts in the wall that expand offstage, out of the audience's view, into fuller rooms only visible though camera work. Maria's bedroom, and the stairway leading to it, are completely offstage.

Van Hove similarly incorporated live video into his Broadway production of NETWORK, a play that warned of the shrinking of privacy in a media-frenzied age, and perhaps the visuals are more effective for those sitting up front, but from this reviewer's mid-orchestra seat the novelty outweighed the drama as they completely took focus from the main action.

As Jets leader Riff (excellent Dharon E. Jones, who allows fear to permeate exterior toughness) leads his gang in singing and dancing "Cool", the blurry view competes with the clear and interesting scene of their girlfriends in the soda shop, tensely waiting for them.

When Maria (Shereen Pimentel displaying a powerful dramatic soprano) sings "I Have A Love" the screen is flooded with a pre-recorded closeup of her and Tony's faces as they kiss in bed. Fortunately for Isaac Powell, a very likable and pleasantly sung Tony, his solo "Maria" is performed without such distractions. Just him downstage singing. What a novel idea.

The videos also supply somewhat skewered social commentary, like when the backdrop for Bernardo (Amar Ramasar) and Anita (Yesenia Ayala) leading their fellow Puerto Ricans in "America" includes scenes from the U.S./Mexico border wall, or when "Gee Officer Krupke" is enhanced with views of citizens using their phones to record instances of police brutality. (On the plus side, Danny Wolohan's Officer Krupke is depicted as a serious threat.)

Even the scene-setting images seem a bit off. Sure, the west side of Manhattan is a lot different now than it was in 1957, and we wouldn't expect the Jets and Sharks to rumble in the middle of Lincoln Center, but the wide, empty streets with an elevated train moving in the background look more like a scene out of industrial Brooklyn.

Attempts at symbolism come off ridiculously. As Tony and Maria sing the soaring "Tonight", the other characters physically try and pull them apart as the two lovers lean into each other to sing the final notes. As "Somewhere" is sung, it looks like dead bodies of gang members are coming to life and making love. Onstage rain falls throughout most of the second half.

And then there's that scene where the Jets rape Anita, usually done as a stylized dance that suggests an attempted rape, here realistically done and projected in large and graphic closeups.

While diverse casting should be encouraged and congratulated, making the Jets a gang primarily made up of people of color while retaining a moment when the Sharks taunt them with slurs aimed at Irish and Italian people is just plain sloppy. Also a bit weird is when Bernardo looks Riff straight in the eye and calls his now African-American foe "native boy." (Another plus is that Zuri Noelle Ford's Anybodys is portrayed as a buff and confident black woman.)

And while we can suspend disbelief to accept a young gang member in 2020 using the phrase "daddy-o", can we draw the line at "gloriosky"?

There are other scattered visuals that work against the script. When the Jets tell Anita that Doc has went to the bank, she still counters that it's night and the banks are closed instead of assuming he's using an ATM. And, despite what they yell out at the dance at the gym, are the Sharks really dancing a mambo?

Could be. Who knows?

Videos