- Wake Up With BroadwayWorld July 28, 2025- A CHORUS LINE Celebrates 50 Years and More

- WICKED: FOR GOOD Merchandise Guide: Toys, Books, Clothes, & More

- Exclusive: Oh My Pod U Guys- Secretary Sixty-Nine with Vicki Lewis

Latest News

Trending Stories

Recommended for You

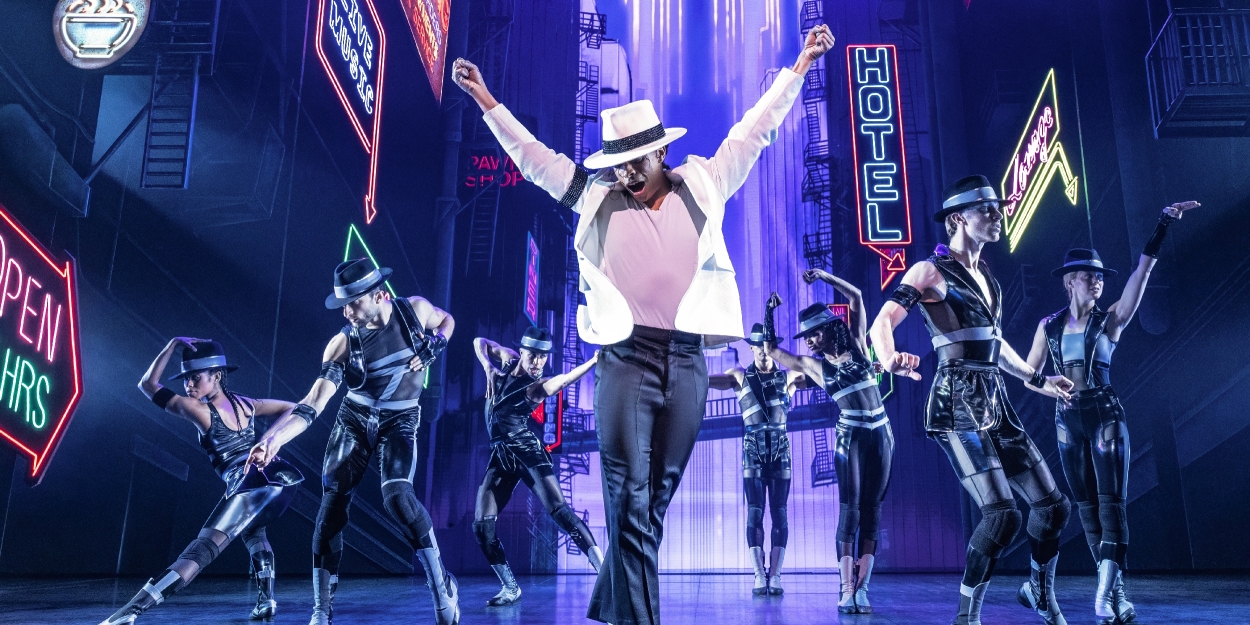

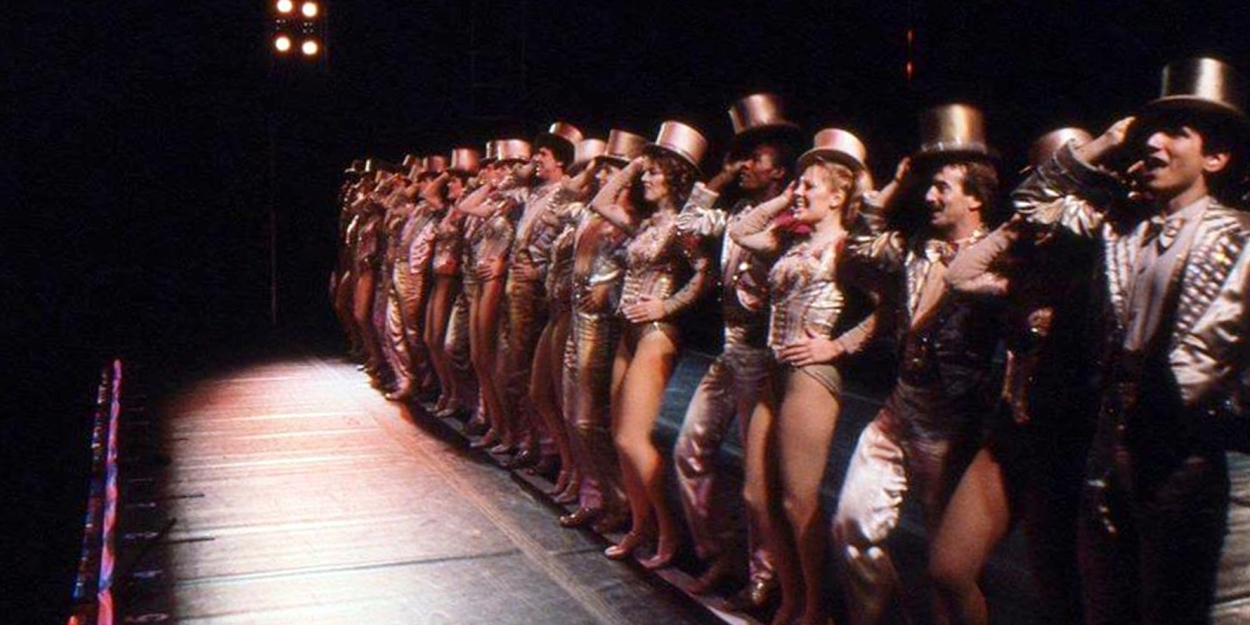

Video: A CHORUS LINE Celebrates 50 Years With A Cast Flash Mob in NYC

Original cast members will reunite on Sunday, July 27, 2025 at the Shubert Theatre.

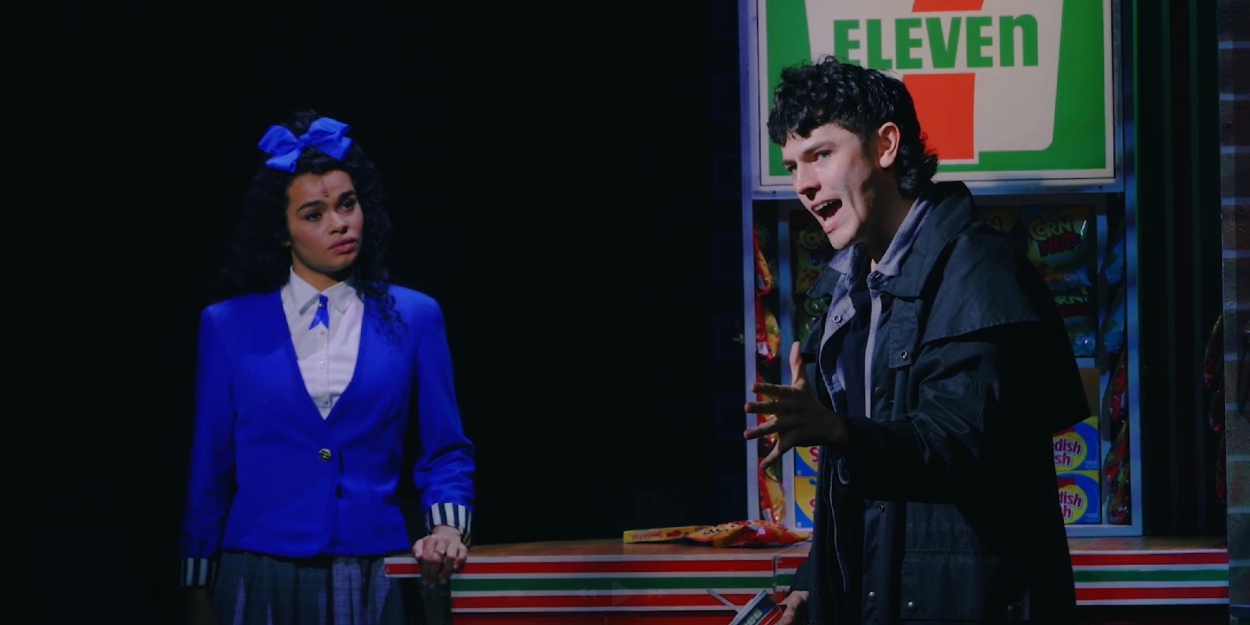

Casting & Cities Announced For THE OUTSIDERS North American Tour

Additional tour stops will be announced at a later date.

Andrew Barth Feldman Will Join MAYBE HAPPY ENDING

Feldman will play the role of “Oliver” beginning on Tuesday, September 2, 2025 for a special limited 9-week run through Saturday, November 1, 2025.

Exclusive: Music, Mirrors & Memories- 4 Cassies Reflect on One of Broadway's Greatest Roles

A Chorus Line opened on Broadway 50 years ago on July 25, 1975.

Ticket Central

Hot Photos this week

Photo: First Look at DOLLY: A TRUE ORIGINAL MUSICAL

Get a First look at Carrie St. Louis as ‘Dolly,’ Katie Rose Clarke as ‘Dolly Parton,’ and Quinn Titcomb as ‘Little Dolly.’

Photo: First Look at DOLLY: A TRUE ORIGINAL MUSICAL

Get a First look at Carrie St. Louis as ‘Dolly,’ Katie Rose Clarke as ‘Dolly Parton,’ and Quinn Titcomb as ‘Little Dolly.’ First Look at EVITA at The Muny

Performances run July 18-24.

First Look at EVITA at The Muny

Performances run July 18-24. Scherzinger and the Cast of SUNSET BLVD. Take Final Bow

The show played its final performance on July 20 at the St. James Theatre following 20 previews and 312 regular performances.

Scherzinger and the Cast of SUNSET BLVD. Take Final Bow

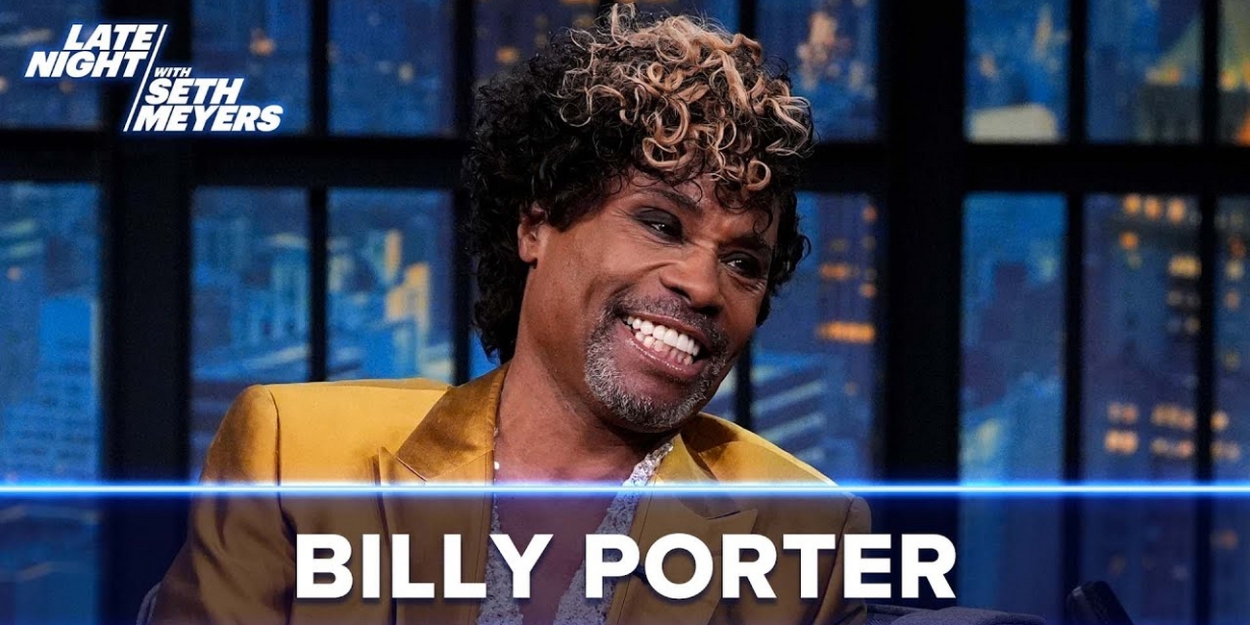

The show played its final performance on July 20 at the St. James Theatre following 20 previews and 312 regular performances. Billy Porter and Marisha Wallace in CABARET

Porter and Wallace begin performances on Tuesday, July 22.

Billy Porter and Marisha Wallace in CABARET

Porter and Wallace begin performances on Tuesday, July 22. The Hollywood Museum Opens Marx Brothers Exhibit LEGENDS OF LAUGHTER

Exhibit features rare memorabilia, original costumes, and family tributes to comedy legends.

The Hollywood Museum Opens Marx Brothers Exhibit LEGENDS OF LAUGHTER

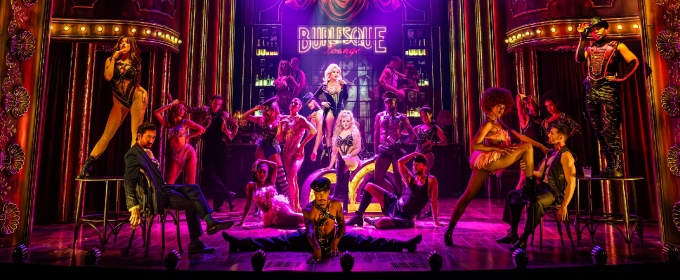

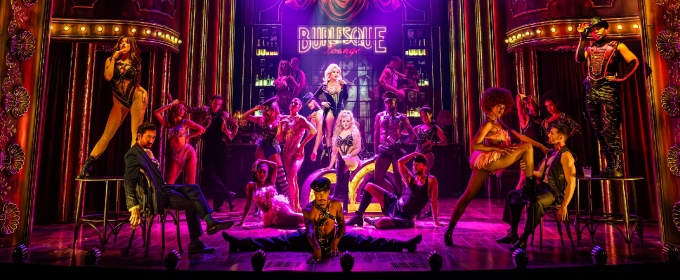

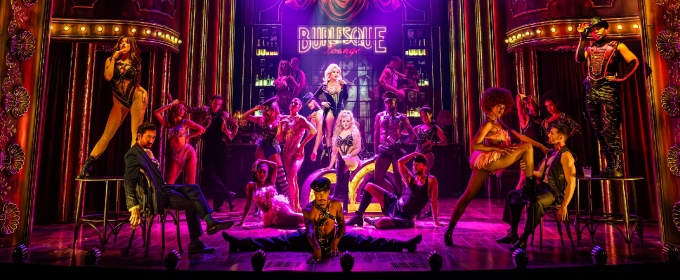

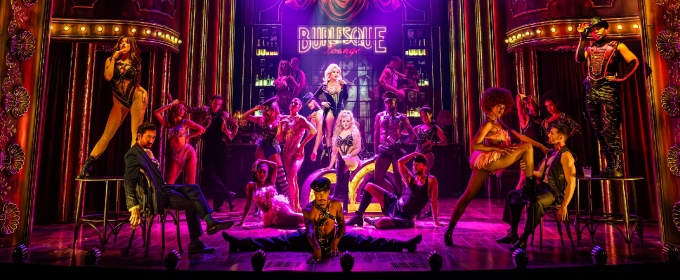

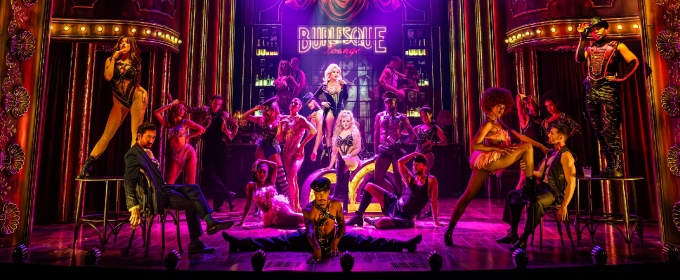

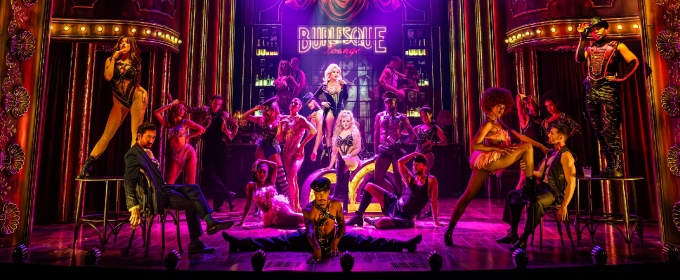

Exhibit features rare memorabilia, original costumes, and family tributes to comedy legends. Jess Folley, Todrick Hall and More in BURLESQUE THE MUSICAL in London

The show plays for a limited season until Saturday 6 September 2025.

Jess Folley, Todrick Hall and More in BURLESQUE THE MUSICAL in London

The show plays for a limited season until Saturday 6 September 2025. First Look at EVITA at The Muny

Performances run July 18-24.

First Look at EVITA at The Muny

Performances run July 18-24. Scherzinger and the Cast of SUNSET BLVD. Take Final Bow

The show played its final performance on July 20 at the St. James Theatre following 20 previews and 312 regular performances.

Scherzinger and the Cast of SUNSET BLVD. Take Final Bow

The show played its final performance on July 20 at the St. James Theatre following 20 previews and 312 regular performances. Billy Porter and Marisha Wallace in CABARET

Porter and Wallace begin performances on Tuesday, July 22.

Billy Porter and Marisha Wallace in CABARET

Porter and Wallace begin performances on Tuesday, July 22. The Hollywood Museum Opens Marx Brothers Exhibit LEGENDS OF LAUGHTER

Exhibit features rare memorabilia, original costumes, and family tributes to comedy legends.

The Hollywood Museum Opens Marx Brothers Exhibit LEGENDS OF LAUGHTER

Exhibit features rare memorabilia, original costumes, and family tributes to comedy legends. Jess Folley, Todrick Hall and More in BURLESQUE THE MUSICAL in London

The show plays for a limited season until Saturday 6 September 2025.

Jess Folley, Todrick Hall and More in BURLESQUE THE MUSICAL in London

The show plays for a limited season until Saturday 6 September 2025. Cole Escola, Sadie Sink, and More at Opening Night of Josh Sharp's TA-DA!

Performances will continue for a limited run through August 23.

Cole Escola, Sadie Sink, and More at Opening Night of Josh Sharp's TA-DA!

Performances will continue for a limited run through August 23. Scherzinger and the Cast of SUNSET BLVD. Take Final Bow

The show played its final performance on July 20 at the St. James Theatre following 20 previews and 312 regular performances.

Scherzinger and the Cast of SUNSET BLVD. Take Final Bow

The show played its final performance on July 20 at the St. James Theatre following 20 previews and 312 regular performances. Billy Porter and Marisha Wallace in CABARET

Porter and Wallace begin performances on Tuesday, July 22.

Billy Porter and Marisha Wallace in CABARET

Porter and Wallace begin performances on Tuesday, July 22. The Hollywood Museum Opens Marx Brothers Exhibit LEGENDS OF LAUGHTER

Exhibit features rare memorabilia, original costumes, and family tributes to comedy legends.

The Hollywood Museum Opens Marx Brothers Exhibit LEGENDS OF LAUGHTER

Exhibit features rare memorabilia, original costumes, and family tributes to comedy legends. Jess Folley, Todrick Hall and More in BURLESQUE THE MUSICAL in London

The show plays for a limited season until Saturday 6 September 2025.

Jess Folley, Todrick Hall and More in BURLESQUE THE MUSICAL in London

The show plays for a limited season until Saturday 6 September 2025. Cole Escola, Sadie Sink, and More at Opening Night of Josh Sharp's TA-DA!

Performances will continue for a limited run through August 23.

Cole Escola, Sadie Sink, and More at Opening Night of Josh Sharp's TA-DA!

Performances will continue for a limited run through August 23. Robyn Hurder, Andrew Durand, and More Star in HIGH SOCIETY at Ogunquit Playhouse

The production runs July 24 through August 23 in Ogunquit, Maine.

Robyn Hurder, Andrew Durand, and More Star in HIGH SOCIETY at Ogunquit Playhouse

The production runs July 24 through August 23 in Ogunquit, Maine.  Billy Porter and Marisha Wallace in CABARET

Porter and Wallace begin performances on Tuesday, July 22.

Billy Porter and Marisha Wallace in CABARET

Porter and Wallace begin performances on Tuesday, July 22. The Hollywood Museum Opens Marx Brothers Exhibit LEGENDS OF LAUGHTER

Exhibit features rare memorabilia, original costumes, and family tributes to comedy legends.

The Hollywood Museum Opens Marx Brothers Exhibit LEGENDS OF LAUGHTER

Exhibit features rare memorabilia, original costumes, and family tributes to comedy legends. Jess Folley, Todrick Hall and More in BURLESQUE THE MUSICAL in London

The show plays for a limited season until Saturday 6 September 2025.

Jess Folley, Todrick Hall and More in BURLESQUE THE MUSICAL in London

The show plays for a limited season until Saturday 6 September 2025. Cole Escola, Sadie Sink, and More at Opening Night of Josh Sharp's TA-DA!

Performances will continue for a limited run through August 23.

Cole Escola, Sadie Sink, and More at Opening Night of Josh Sharp's TA-DA!

Performances will continue for a limited run through August 23. Robyn Hurder, Andrew Durand, and More Star in HIGH SOCIETY at Ogunquit Playhouse

The production runs July 24 through August 23 in Ogunquit, Maine.

Robyn Hurder, Andrew Durand, and More Star in HIGH SOCIETY at Ogunquit Playhouse

The production runs July 24 through August 23 in Ogunquit, Maine.  Phylicia Rashad and the Cast of IMMEDIATE FAMILY Meets the Press

Performances run July 29 through August 31 in the Booth Playhouse in Charlotte, North Carolina.

Phylicia Rashad and the Cast of IMMEDIATE FAMILY Meets the Press

Performances run July 29 through August 31 in the Booth Playhouse in Charlotte, North Carolina. The Hollywood Museum Opens Marx Brothers Exhibit LEGENDS OF LAUGHTER

Exhibit features rare memorabilia, original costumes, and family tributes to comedy legends.

The Hollywood Museum Opens Marx Brothers Exhibit LEGENDS OF LAUGHTER

Exhibit features rare memorabilia, original costumes, and family tributes to comedy legends. Jess Folley, Todrick Hall and More in BURLESQUE THE MUSICAL in London

The show plays for a limited season until Saturday 6 September 2025.

Jess Folley, Todrick Hall and More in BURLESQUE THE MUSICAL in London

The show plays for a limited season until Saturday 6 September 2025. Cole Escola, Sadie Sink, and More at Opening Night of Josh Sharp's TA-DA!

Performances will continue for a limited run through August 23.

Cole Escola, Sadie Sink, and More at Opening Night of Josh Sharp's TA-DA!

Performances will continue for a limited run through August 23. Robyn Hurder, Andrew Durand, and More Star in HIGH SOCIETY at Ogunquit Playhouse

The production runs July 24 through August 23 in Ogunquit, Maine.

Robyn Hurder, Andrew Durand, and More Star in HIGH SOCIETY at Ogunquit Playhouse

The production runs July 24 through August 23 in Ogunquit, Maine.  Phylicia Rashad and the Cast of IMMEDIATE FAMILY Meets the Press

Performances run July 29 through August 31 in the Booth Playhouse in Charlotte, North Carolina.

Phylicia Rashad and the Cast of IMMEDIATE FAMILY Meets the Press

Performances run July 29 through August 31 in the Booth Playhouse in Charlotte, North Carolina. Noah Schnapp Visits STRANGER THINGS on Broadway

The series star joined Tony nominee Louis McCartney, star of the stage show, to surprise Stranger Things fans at the stage door after the performance.

Noah Schnapp Visits STRANGER THINGS on Broadway

The series star joined Tony nominee Louis McCartney, star of the stage show, to surprise Stranger Things fans at the stage door after the performance. Jess Folley, Todrick Hall and More in BURLESQUE THE MUSICAL in London

The show plays for a limited season until Saturday 6 September 2025.

Jess Folley, Todrick Hall and More in BURLESQUE THE MUSICAL in London

The show plays for a limited season until Saturday 6 September 2025. Cole Escola, Sadie Sink, and More at Opening Night of Josh Sharp's TA-DA!

Performances will continue for a limited run through August 23.

Cole Escola, Sadie Sink, and More at Opening Night of Josh Sharp's TA-DA!

Performances will continue for a limited run through August 23. Robyn Hurder, Andrew Durand, and More Star in HIGH SOCIETY at Ogunquit Playhouse

The production runs July 24 through August 23 in Ogunquit, Maine.

Robyn Hurder, Andrew Durand, and More Star in HIGH SOCIETY at Ogunquit Playhouse

The production runs July 24 through August 23 in Ogunquit, Maine.  Phylicia Rashad and the Cast of IMMEDIATE FAMILY Meets the Press

Performances run July 29 through August 31 in the Booth Playhouse in Charlotte, North Carolina.

Phylicia Rashad and the Cast of IMMEDIATE FAMILY Meets the Press

Performances run July 29 through August 31 in the Booth Playhouse in Charlotte, North Carolina. Noah Schnapp Visits STRANGER THINGS on Broadway

The series star joined Tony nominee Louis McCartney, star of the stage show, to surprise Stranger Things fans at the stage door after the performance.

Noah Schnapp Visits STRANGER THINGS on Broadway

The series star joined Tony nominee Louis McCartney, star of the stage show, to surprise Stranger Things fans at the stage door after the performance. First Look at the Revitalized Delacorte Theater

The Delacorte will officially reopen to the public on August 7, with Twelfth Night.

First Look at the Revitalized Delacorte Theater

The Delacorte will officially reopen to the public on August 7, with Twelfth Night. Cole Escola, Sadie Sink, and More at Opening Night of Josh Sharp's TA-DA!

Performances will continue for a limited run through August 23.

Cole Escola, Sadie Sink, and More at Opening Night of Josh Sharp's TA-DA!

Performances will continue for a limited run through August 23. Robyn Hurder, Andrew Durand, and More Star in HIGH SOCIETY at Ogunquit Playhouse

The production runs July 24 through August 23 in Ogunquit, Maine.

Robyn Hurder, Andrew Durand, and More Star in HIGH SOCIETY at Ogunquit Playhouse

The production runs July 24 through August 23 in Ogunquit, Maine.  Phylicia Rashad and the Cast of IMMEDIATE FAMILY Meets the Press

Performances run July 29 through August 31 in the Booth Playhouse in Charlotte, North Carolina.

Phylicia Rashad and the Cast of IMMEDIATE FAMILY Meets the Press

Performances run July 29 through August 31 in the Booth Playhouse in Charlotte, North Carolina. Noah Schnapp Visits STRANGER THINGS on Broadway

The series star joined Tony nominee Louis McCartney, star of the stage show, to surprise Stranger Things fans at the stage door after the performance.

Noah Schnapp Visits STRANGER THINGS on Broadway

The series star joined Tony nominee Louis McCartney, star of the stage show, to surprise Stranger Things fans at the stage door after the performance. First Look at the Revitalized Delacorte Theater

The Delacorte will officially reopen to the public on August 7, with Twelfth Night.

First Look at the Revitalized Delacorte Theater

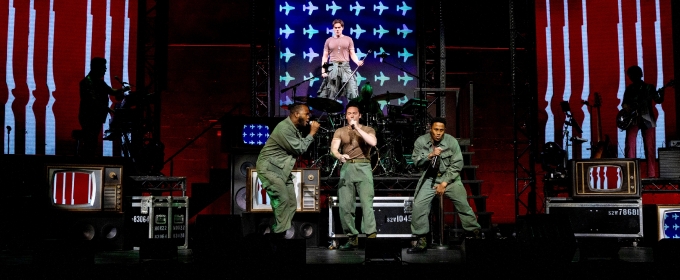

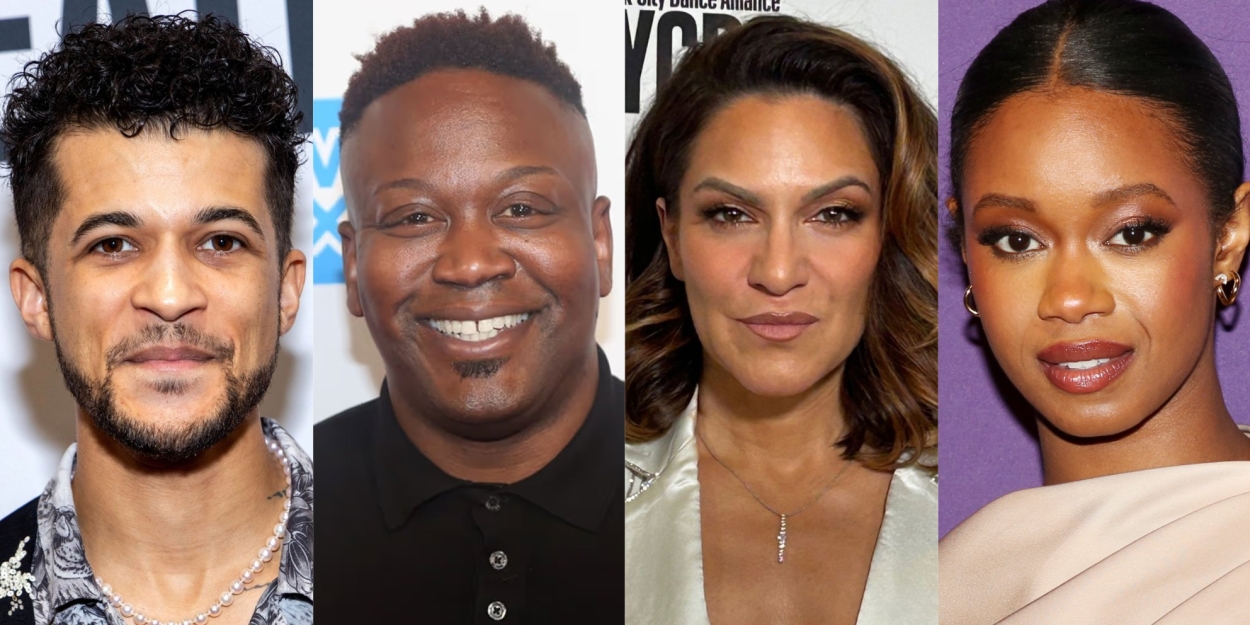

The Delacorte will officially reopen to the public on August 7, with Twelfth Night. Wayne Brady and Taye Diggs Join the Cast of MOULIN ROUGE! THE MUSICAL

Diggs plays through September 28, with Brady staying through November 9.

Wayne Brady and Taye Diggs Join the Cast of MOULIN ROUGE! THE MUSICAL

Diggs plays through September 28, with Brady staying through November 9. Robyn Hurder, Andrew Durand, and More Star in HIGH SOCIETY at Ogunquit Playhouse

The production runs July 24 through August 23 in Ogunquit, Maine.

Robyn Hurder, Andrew Durand, and More Star in HIGH SOCIETY at Ogunquit Playhouse

The production runs July 24 through August 23 in Ogunquit, Maine.  Phylicia Rashad and the Cast of IMMEDIATE FAMILY Meets the Press

Performances run July 29 through August 31 in the Booth Playhouse in Charlotte, North Carolina.

Phylicia Rashad and the Cast of IMMEDIATE FAMILY Meets the Press

Performances run July 29 through August 31 in the Booth Playhouse in Charlotte, North Carolina. Noah Schnapp Visits STRANGER THINGS on Broadway

The series star joined Tony nominee Louis McCartney, star of the stage show, to surprise Stranger Things fans at the stage door after the performance.

Noah Schnapp Visits STRANGER THINGS on Broadway

The series star joined Tony nominee Louis McCartney, star of the stage show, to surprise Stranger Things fans at the stage door after the performance. First Look at the Revitalized Delacorte Theater

The Delacorte will officially reopen to the public on August 7, with Twelfth Night.

First Look at the Revitalized Delacorte Theater

The Delacorte will officially reopen to the public on August 7, with Twelfth Night. Wayne Brady and Taye Diggs Join the Cast of MOULIN ROUGE! THE MUSICAL

Diggs plays through September 28, with Brady staying through November 9.

Wayne Brady and Taye Diggs Join the Cast of MOULIN ROUGE! THE MUSICAL

Diggs plays through September 28, with Brady staying through November 9. Sadie Sink Takes Final Bow in JOHN PROCTOR IS THE VILLAIN

She played her final performance on Sunday, July 13.

Sadie Sink Takes Final Bow in JOHN PROCTOR IS THE VILLAIN

She played her final performance on Sunday, July 13. Phylicia Rashad and the Cast of IMMEDIATE FAMILY Meets the Press

Performances run July 29 through August 31 in the Booth Playhouse in Charlotte, North Carolina.

Phylicia Rashad and the Cast of IMMEDIATE FAMILY Meets the Press

Performances run July 29 through August 31 in the Booth Playhouse in Charlotte, North Carolina. Noah Schnapp Visits STRANGER THINGS on Broadway

The series star joined Tony nominee Louis McCartney, star of the stage show, to surprise Stranger Things fans at the stage door after the performance.

Noah Schnapp Visits STRANGER THINGS on Broadway

The series star joined Tony nominee Louis McCartney, star of the stage show, to surprise Stranger Things fans at the stage door after the performance. First Look at the Revitalized Delacorte Theater

The Delacorte will officially reopen to the public on August 7, with Twelfth Night.

First Look at the Revitalized Delacorte Theater

The Delacorte will officially reopen to the public on August 7, with Twelfth Night. Wayne Brady and Taye Diggs Join the Cast of MOULIN ROUGE! THE MUSICAL

Diggs plays through September 28, with Brady staying through November 9.

Wayne Brady and Taye Diggs Join the Cast of MOULIN ROUGE! THE MUSICAL

Diggs plays through September 28, with Brady staying through November 9. Sadie Sink Takes Final Bow in JOHN PROCTOR IS THE VILLAIN

She played her final performance on Sunday, July 13.

Sadie Sink Takes Final Bow in JOHN PROCTOR IS THE VILLAIN

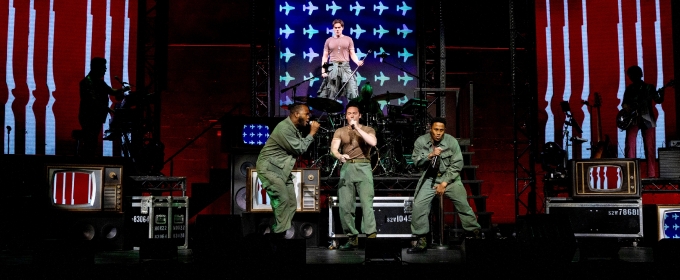

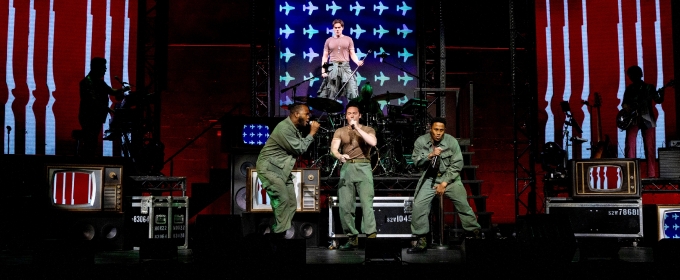

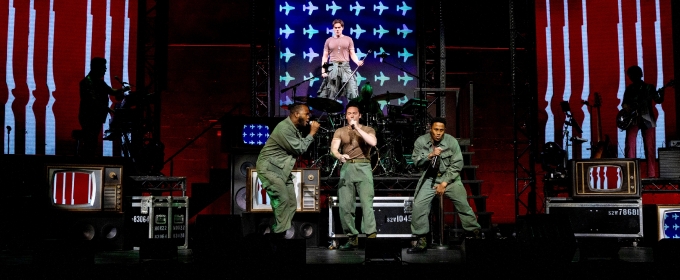

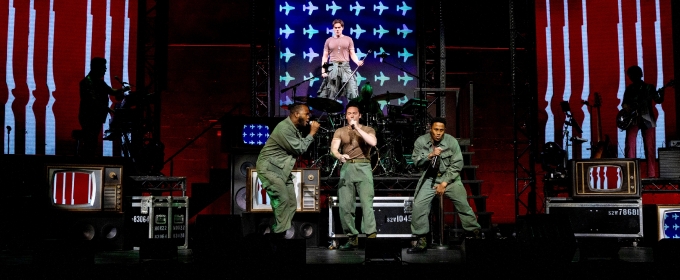

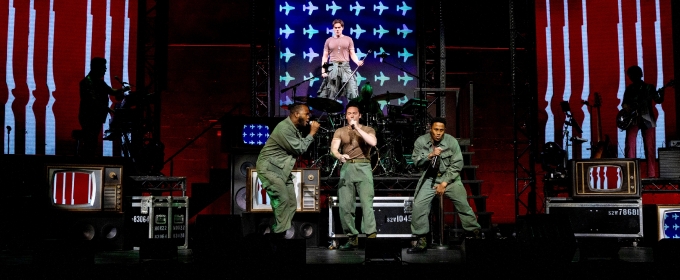

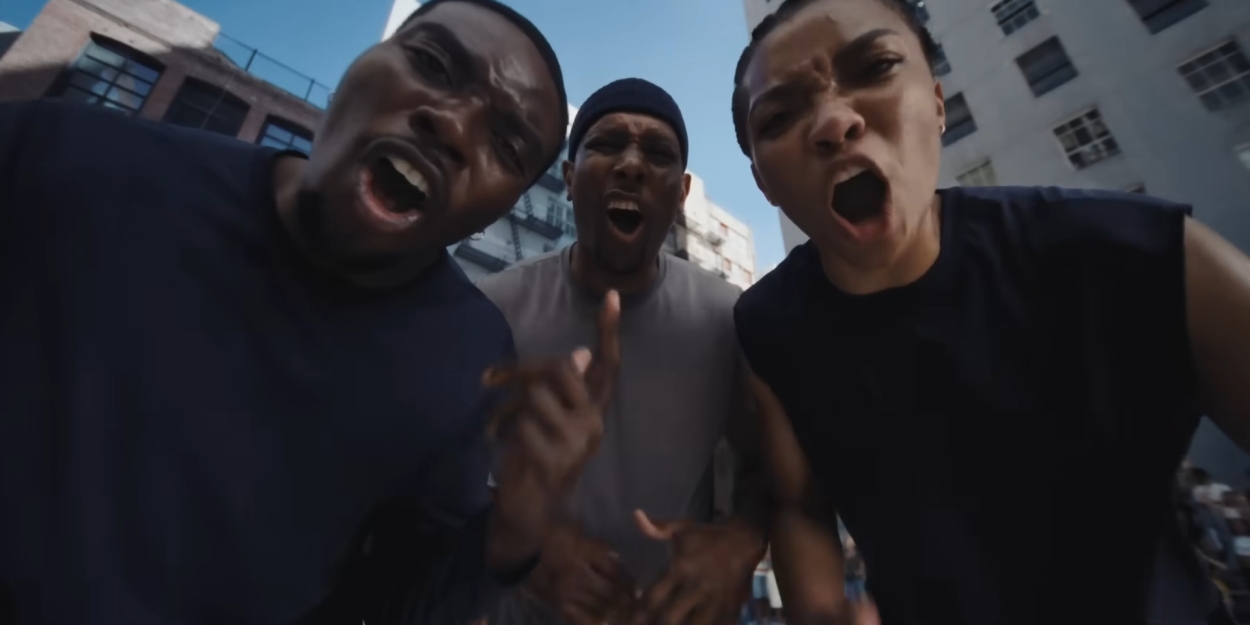

She played her final performance on Sunday, July 13. First Look at ROLLING THUNDER Musical Off-Broadway

Rolling Thunder began performances on Thursday, July 10 at New World Stages (340 W 50th St) ahead of its Thursday, July 24 opening.

First Look at ROLLING THUNDER Musical Off-Broadway

Rolling Thunder began performances on Thursday, July 10 at New World Stages (340 W 50th St) ahead of its Thursday, July 24 opening. Noah Schnapp Visits STRANGER THINGS on Broadway

The series star joined Tony nominee Louis McCartney, star of the stage show, to surprise Stranger Things fans at the stage door after the performance.

Noah Schnapp Visits STRANGER THINGS on Broadway

The series star joined Tony nominee Louis McCartney, star of the stage show, to surprise Stranger Things fans at the stage door after the performance. First Look at the Revitalized Delacorte Theater

The Delacorte will officially reopen to the public on August 7, with Twelfth Night.

First Look at the Revitalized Delacorte Theater

The Delacorte will officially reopen to the public on August 7, with Twelfth Night. Wayne Brady and Taye Diggs Join the Cast of MOULIN ROUGE! THE MUSICAL

Diggs plays through September 28, with Brady staying through November 9.

Wayne Brady and Taye Diggs Join the Cast of MOULIN ROUGE! THE MUSICAL

Diggs plays through September 28, with Brady staying through November 9. Sadie Sink Takes Final Bow in JOHN PROCTOR IS THE VILLAIN

She played her final performance on Sunday, July 13.

Sadie Sink Takes Final Bow in JOHN PROCTOR IS THE VILLAIN

She played her final performance on Sunday, July 13. First Look at ROLLING THUNDER Musical Off-Broadway

Rolling Thunder began performances on Thursday, July 10 at New World Stages (340 W 50th St) ahead of its Thursday, July 24 opening.

First Look at ROLLING THUNDER Musical Off-Broadway

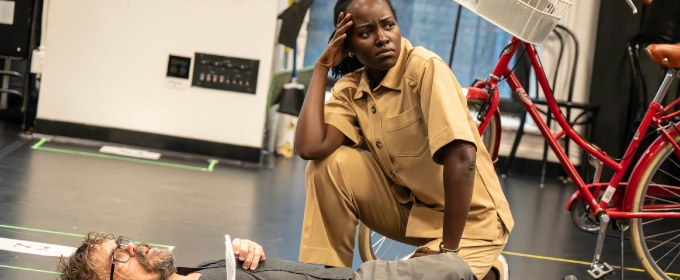

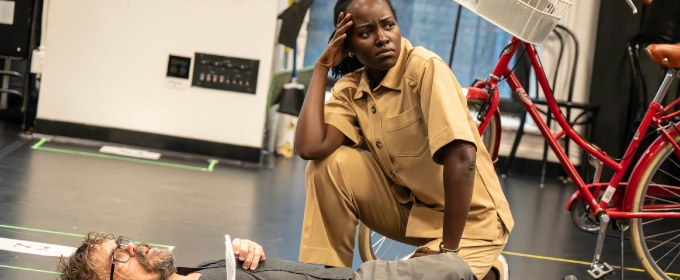

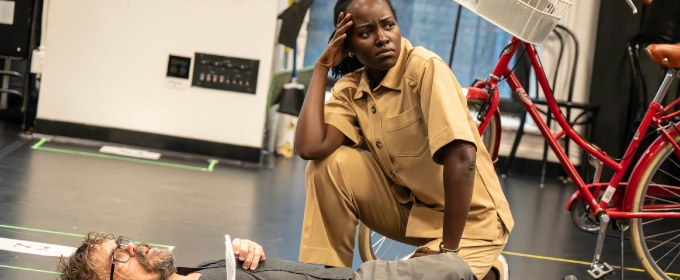

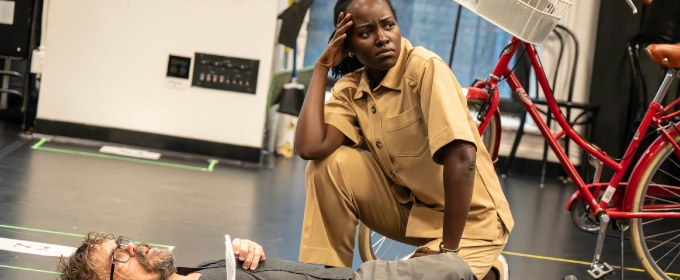

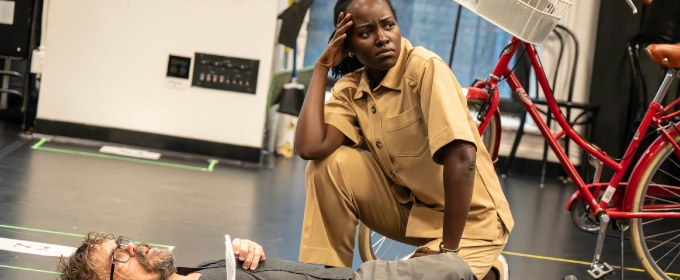

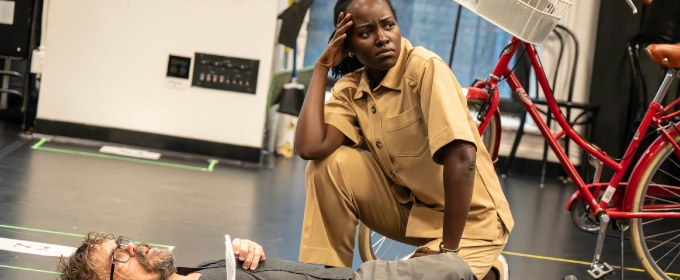

Rolling Thunder began performances on Thursday, July 10 at New World Stages (340 W 50th St) ahead of its Thursday, July 24 opening. In Rehearsals for Shakespeare in the Park's TWELFTH NIGHT

Twelfth Night will run August 7 through September 14, 2025.

In Rehearsals for Shakespeare in the Park's TWELFTH NIGHT

Twelfth Night will run August 7 through September 14, 2025. First Look at the Revitalized Delacorte Theater

The Delacorte will officially reopen to the public on August 7, with Twelfth Night.

First Look at the Revitalized Delacorte Theater

The Delacorte will officially reopen to the public on August 7, with Twelfth Night. Wayne Brady and Taye Diggs Join the Cast of MOULIN ROUGE! THE MUSICAL

Diggs plays through September 28, with Brady staying through November 9.

Wayne Brady and Taye Diggs Join the Cast of MOULIN ROUGE! THE MUSICAL

Diggs plays through September 28, with Brady staying through November 9. Sadie Sink Takes Final Bow in JOHN PROCTOR IS THE VILLAIN

She played her final performance on Sunday, July 13.

Sadie Sink Takes Final Bow in JOHN PROCTOR IS THE VILLAIN

She played her final performance on Sunday, July 13. First Look at ROLLING THUNDER Musical Off-Broadway

Rolling Thunder began performances on Thursday, July 10 at New World Stages (340 W 50th St) ahead of its Thursday, July 24 opening.

First Look at ROLLING THUNDER Musical Off-Broadway

Rolling Thunder began performances on Thursday, July 10 at New World Stages (340 W 50th St) ahead of its Thursday, July 24 opening. In Rehearsals for Shakespeare in the Park's TWELFTH NIGHT

Twelfth Night will run August 7 through September 14, 2025.

In Rehearsals for Shakespeare in the Park's TWELFTH NIGHT

Twelfth Night will run August 7 through September 14, 2025. GINGER TWINSIES World Premiere First Look

Performances began on July 10, 2025, for the strictly limited, 16-week engagement through October 26, 2025.

GINGER TWINSIES World Premiere First Look

Performances began on July 10, 2025, for the strictly limited, 16-week engagement through October 26, 2025. Wayne Brady and Taye Diggs Join the Cast of MOULIN ROUGE! THE MUSICAL

Diggs plays through September 28, with Brady staying through November 9.

Wayne Brady and Taye Diggs Join the Cast of MOULIN ROUGE! THE MUSICAL

Diggs plays through September 28, with Brady staying through November 9. Sadie Sink Takes Final Bow in JOHN PROCTOR IS THE VILLAIN

She played her final performance on Sunday, July 13.

Sadie Sink Takes Final Bow in JOHN PROCTOR IS THE VILLAIN

She played her final performance on Sunday, July 13. First Look at ROLLING THUNDER Musical Off-Broadway

Rolling Thunder began performances on Thursday, July 10 at New World Stages (340 W 50th St) ahead of its Thursday, July 24 opening.

First Look at ROLLING THUNDER Musical Off-Broadway

Rolling Thunder began performances on Thursday, July 10 at New World Stages (340 W 50th St) ahead of its Thursday, July 24 opening. In Rehearsals for Shakespeare in the Park's TWELFTH NIGHT

Twelfth Night will run August 7 through September 14, 2025.

In Rehearsals for Shakespeare in the Park's TWELFTH NIGHT

Twelfth Night will run August 7 through September 14, 2025. GINGER TWINSIES World Premiere First Look

Performances began on July 10, 2025, for the strictly limited, 16-week engagement through October 26, 2025.

GINGER TWINSIES World Premiere First Look

Performances began on July 10, 2025, for the strictly limited, 16-week engagement through October 26, 2025. Blank Theatre Company Presents PASSION

Performances will run through August 10th.

Blank Theatre Company Presents PASSION

Performances will run through August 10th. Sadie Sink Takes Final Bow in JOHN PROCTOR IS THE VILLAIN

She played her final performance on Sunday, July 13.

Sadie Sink Takes Final Bow in JOHN PROCTOR IS THE VILLAIN

She played her final performance on Sunday, July 13. First Look at ROLLING THUNDER Musical Off-Broadway

Rolling Thunder began performances on Thursday, July 10 at New World Stages (340 W 50th St) ahead of its Thursday, July 24 opening.

First Look at ROLLING THUNDER Musical Off-Broadway

Rolling Thunder began performances on Thursday, July 10 at New World Stages (340 W 50th St) ahead of its Thursday, July 24 opening. In Rehearsals for Shakespeare in the Park's TWELFTH NIGHT

Twelfth Night will run August 7 through September 14, 2025.

In Rehearsals for Shakespeare in the Park's TWELFTH NIGHT

Twelfth Night will run August 7 through September 14, 2025. GINGER TWINSIES World Premiere First Look

Performances began on July 10, 2025, for the strictly limited, 16-week engagement through October 26, 2025.

GINGER TWINSIES World Premiere First Look

Performances began on July 10, 2025, for the strictly limited, 16-week engagement through October 26, 2025. Blank Theatre Company Presents PASSION

Performances will run through August 10th.

Blank Theatre Company Presents PASSION

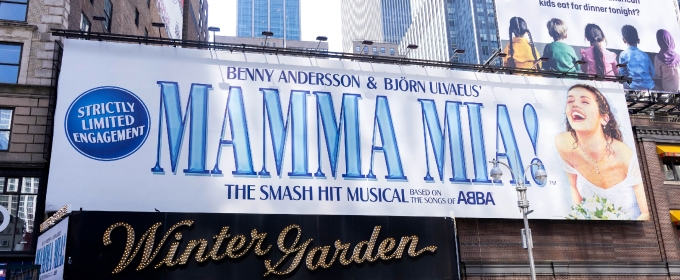

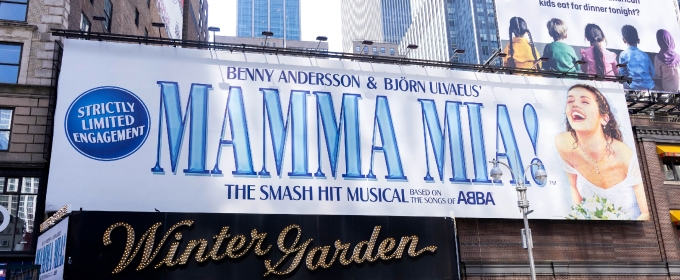

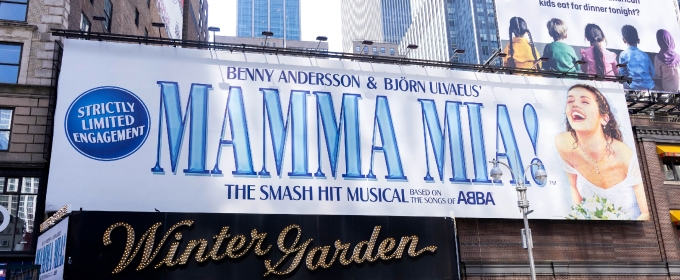

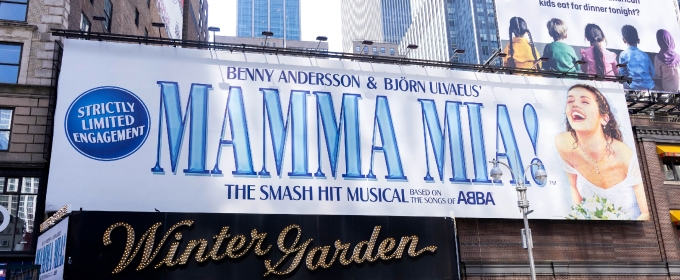

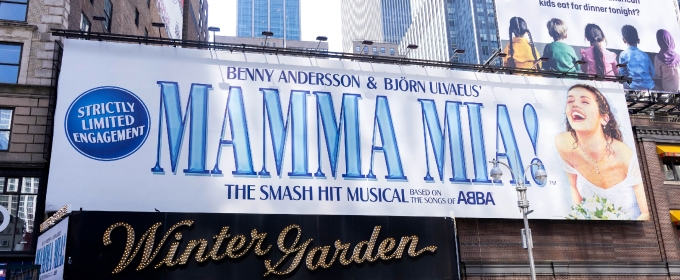

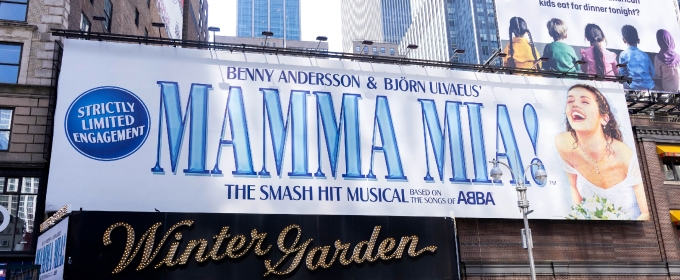

Performances will run through August 10th. MAMMA MIA! Returns to the Winter Garden Theatre

The limited engagement will play for six months only, through Sunday, February 1, 2026.

MAMMA MIA! Returns to the Winter Garden Theatre

The limited engagement will play for six months only, through Sunday, February 1, 2026. First Look at ROLLING THUNDER Musical Off-Broadway

Rolling Thunder began performances on Thursday, July 10 at New World Stages (340 W 50th St) ahead of its Thursday, July 24 opening.

First Look at ROLLING THUNDER Musical Off-Broadway

Rolling Thunder began performances on Thursday, July 10 at New World Stages (340 W 50th St) ahead of its Thursday, July 24 opening. In Rehearsals for Shakespeare in the Park's TWELFTH NIGHT

Twelfth Night will run August 7 through September 14, 2025.

In Rehearsals for Shakespeare in the Park's TWELFTH NIGHT

Twelfth Night will run August 7 through September 14, 2025. GINGER TWINSIES World Premiere First Look

Performances began on July 10, 2025, for the strictly limited, 16-week engagement through October 26, 2025.

GINGER TWINSIES World Premiere First Look

Performances began on July 10, 2025, for the strictly limited, 16-week engagement through October 26, 2025. Blank Theatre Company Presents PASSION

Performances will run through August 10th.

Blank Theatre Company Presents PASSION

Performances will run through August 10th. MAMMA MIA! Returns to the Winter Garden Theatre

The limited engagement will play for six months only, through Sunday, February 1, 2026.

MAMMA MIA! Returns to the Winter Garden Theatre

The limited engagement will play for six months only, through Sunday, February 1, 2026. Review: CAMELOT at Brookfield Theatre

What did our critic think of CAMELOT at Brookfield Theatre?

Review: CAMELOT at Brookfield Theatre

What did our critic think of CAMELOT at Brookfield Theatre? In Rehearsals for Shakespeare in the Park's TWELFTH NIGHT

Twelfth Night will run August 7 through September 14, 2025.

In Rehearsals for Shakespeare in the Park's TWELFTH NIGHT

Twelfth Night will run August 7 through September 14, 2025. GINGER TWINSIES World Premiere First Look

Performances began on July 10, 2025, for the strictly limited, 16-week engagement through October 26, 2025.

GINGER TWINSIES World Premiere First Look

Performances began on July 10, 2025, for the strictly limited, 16-week engagement through October 26, 2025. Blank Theatre Company Presents PASSION

Performances will run through August 10th.

Blank Theatre Company Presents PASSION

Performances will run through August 10th. MAMMA MIA! Returns to the Winter Garden Theatre

The limited engagement will play for six months only, through Sunday, February 1, 2026.

MAMMA MIA! Returns to the Winter Garden Theatre

The limited engagement will play for six months only, through Sunday, February 1, 2026. Review: CAMELOT at Brookfield Theatre

What did our critic think of CAMELOT at Brookfield Theatre?

Review: CAMELOT at Brookfield Theatre

What did our critic think of CAMELOT at Brookfield Theatre? GINGER TWINSIES Celebrates Its Star-Studded Opening Night

The cast was joined by many familiar faces including Jesse Tyler Ferguson, Lin-Manuel Miranda, Busy Phillips, and more.

GINGER TWINSIES Celebrates Its Star-Studded Opening Night

The cast was joined by many familiar faces including Jesse Tyler Ferguson, Lin-Manuel Miranda, Busy Phillips, and more. GINGER TWINSIES World Premiere First Look

Performances began on July 10, 2025, for the strictly limited, 16-week engagement through October 26, 2025.

GINGER TWINSIES World Premiere First Look

Performances began on July 10, 2025, for the strictly limited, 16-week engagement through October 26, 2025. Blank Theatre Company Presents PASSION

Performances will run through August 10th.

Blank Theatre Company Presents PASSION

Performances will run through August 10th. MAMMA MIA! Returns to the Winter Garden Theatre

The limited engagement will play for six months only, through Sunday, February 1, 2026.

MAMMA MIA! Returns to the Winter Garden Theatre

The limited engagement will play for six months only, through Sunday, February 1, 2026. Review: CAMELOT at Brookfield Theatre

What did our critic think of CAMELOT at Brookfield Theatre?

Review: CAMELOT at Brookfield Theatre

What did our critic think of CAMELOT at Brookfield Theatre? GINGER TWINSIES Celebrates Its Star-Studded Opening Night

The cast was joined by many familiar faces including Jesse Tyler Ferguson, Lin-Manuel Miranda, Busy Phillips, and more.

GINGER TWINSIES Celebrates Its Star-Studded Opening Night

The cast was joined by many familiar faces including Jesse Tyler Ferguson, Lin-Manuel Miranda, Busy Phillips, and more. First Look At Brenda Pressley As 'Claudine Jasper' In PURPOSE

Pressley steps into the role of Claudine Jasper beginning July 15.

First Look At Brenda Pressley As 'Claudine Jasper' In PURPOSE

Pressley steps into the role of Claudine Jasper beginning July 15. Blank Theatre Company Presents PASSION

Performances will run through August 10th.

Blank Theatre Company Presents PASSION

Performances will run through August 10th. MAMMA MIA! Returns to the Winter Garden Theatre

The limited engagement will play for six months only, through Sunday, February 1, 2026.

MAMMA MIA! Returns to the Winter Garden Theatre

The limited engagement will play for six months only, through Sunday, February 1, 2026. Review: CAMELOT at Brookfield Theatre

What did our critic think of CAMELOT at Brookfield Theatre?

Review: CAMELOT at Brookfield Theatre

What did our critic think of CAMELOT at Brookfield Theatre? GINGER TWINSIES Celebrates Its Star-Studded Opening Night

The cast was joined by many familiar faces including Jesse Tyler Ferguson, Lin-Manuel Miranda, Busy Phillips, and more.

GINGER TWINSIES Celebrates Its Star-Studded Opening Night

The cast was joined by many familiar faces including Jesse Tyler Ferguson, Lin-Manuel Miranda, Busy Phillips, and more. First Look At Brenda Pressley As 'Claudine Jasper' In PURPOSE

Pressley steps into the role of Claudine Jasper beginning July 15.

First Look At Brenda Pressley As 'Claudine Jasper' In PURPOSE

Pressley steps into the role of Claudine Jasper beginning July 15. Porter and Wallace Meet the Press Ahead of CABARET Run

They began performances on Tuesday, July 22 and continue for the production’s final 13 weeks through Sunday, October 19.

Porter and Wallace Meet the Press Ahead of CABARET Run

They began performances on Tuesday, July 22 and continue for the production’s final 13 weeks through Sunday, October 19. MAMMA MIA! Returns to the Winter Garden Theatre

The limited engagement will play for six months only, through Sunday, February 1, 2026.

MAMMA MIA! Returns to the Winter Garden Theatre

The limited engagement will play for six months only, through Sunday, February 1, 2026. Review: CAMELOT at Brookfield Theatre

What did our critic think of CAMELOT at Brookfield Theatre?

Review: CAMELOT at Brookfield Theatre

What did our critic think of CAMELOT at Brookfield Theatre? GINGER TWINSIES Celebrates Its Star-Studded Opening Night

The cast was joined by many familiar faces including Jesse Tyler Ferguson, Lin-Manuel Miranda, Busy Phillips, and more.

GINGER TWINSIES Celebrates Its Star-Studded Opening Night

The cast was joined by many familiar faces including Jesse Tyler Ferguson, Lin-Manuel Miranda, Busy Phillips, and more. First Look At Brenda Pressley As 'Claudine Jasper' In PURPOSE

Pressley steps into the role of Claudine Jasper beginning July 15.

First Look At Brenda Pressley As 'Claudine Jasper' In PURPOSE

Pressley steps into the role of Claudine Jasper beginning July 15. Porter and Wallace Meet the Press Ahead of CABARET Run

They began performances on Tuesday, July 22 and continue for the production’s final 13 weeks through Sunday, October 19.

Porter and Wallace Meet the Press Ahead of CABARET Run

They began performances on Tuesday, July 22 and continue for the production’s final 13 weeks through Sunday, October 19. Frankie Grande Visits STRANGER THINGS: THE FIRST SHADOW

He saw the show two days in a row this week, bringing his mother Joan to the show to meet the cast as well.

Frankie Grande Visits STRANGER THINGS: THE FIRST SHADOW

He saw the show two days in a row this week, bringing his mother Joan to the show to meet the cast as well. Review: CAMELOT at Brookfield Theatre

What did our critic think of CAMELOT at Brookfield Theatre?

Review: CAMELOT at Brookfield Theatre

What did our critic think of CAMELOT at Brookfield Theatre? GINGER TWINSIES Celebrates Its Star-Studded Opening Night

The cast was joined by many familiar faces including Jesse Tyler Ferguson, Lin-Manuel Miranda, Busy Phillips, and more.

GINGER TWINSIES Celebrates Its Star-Studded Opening Night

The cast was joined by many familiar faces including Jesse Tyler Ferguson, Lin-Manuel Miranda, Busy Phillips, and more. First Look At Brenda Pressley As 'Claudine Jasper' In PURPOSE

Pressley steps into the role of Claudine Jasper beginning July 15.

First Look At Brenda Pressley As 'Claudine Jasper' In PURPOSE

Pressley steps into the role of Claudine Jasper beginning July 15. Porter and Wallace Meet the Press Ahead of CABARET Run

They began performances on Tuesday, July 22 and continue for the production’s final 13 weeks through Sunday, October 19.

Porter and Wallace Meet the Press Ahead of CABARET Run

They began performances on Tuesday, July 22 and continue for the production’s final 13 weeks through Sunday, October 19. Frankie Grande Visits STRANGER THINGS: THE FIRST SHADOW

He saw the show two days in a row this week, bringing his mother Joan to the show to meet the cast as well.

Frankie Grande Visits STRANGER THINGS: THE FIRST SHADOW

He saw the show two days in a row this week, bringing his mother Joan to the show to meet the cast as well. On the Opening Night Red Carpet for GINGER TWINSIES

Ginger Twinsies is running off-Broadway at the Orpheum Theatre.

On the Opening Night Red Carpet for GINGER TWINSIES

Ginger Twinsies is running off-Broadway at the Orpheum Theatre. GINGER TWINSIES Celebrates Its Star-Studded Opening Night

The cast was joined by many familiar faces including Jesse Tyler Ferguson, Lin-Manuel Miranda, Busy Phillips, and more.

GINGER TWINSIES Celebrates Its Star-Studded Opening Night

The cast was joined by many familiar faces including Jesse Tyler Ferguson, Lin-Manuel Miranda, Busy Phillips, and more. First Look At Brenda Pressley As 'Claudine Jasper' In PURPOSE

Pressley steps into the role of Claudine Jasper beginning July 15.

First Look At Brenda Pressley As 'Claudine Jasper' In PURPOSE

Pressley steps into the role of Claudine Jasper beginning July 15. Porter and Wallace Meet the Press Ahead of CABARET Run

They began performances on Tuesday, July 22 and continue for the production’s final 13 weeks through Sunday, October 19.

Porter and Wallace Meet the Press Ahead of CABARET Run

They began performances on Tuesday, July 22 and continue for the production’s final 13 weeks through Sunday, October 19. Frankie Grande Visits STRANGER THINGS: THE FIRST SHADOW

He saw the show two days in a row this week, bringing his mother Joan to the show to meet the cast as well.

Frankie Grande Visits STRANGER THINGS: THE FIRST SHADOW

He saw the show two days in a row this week, bringing his mother Joan to the show to meet the cast as well. On the Opening Night Red Carpet for GINGER TWINSIES

Ginger Twinsies is running off-Broadway at the Orpheum Theatre.

On the Opening Night Red Carpet for GINGER TWINSIES

Ginger Twinsies is running off-Broadway at the Orpheum Theatre. First Look at ROLLING THUNDER Off-Broadway

Rolling Thunder will open July 24 at New World Stages.

First Look at ROLLING THUNDER Off-Broadway

Rolling Thunder will open July 24 at New World Stages. First Look At Brenda Pressley As 'Claudine Jasper' In PURPOSE

Pressley steps into the role of Claudine Jasper beginning July 15.

First Look At Brenda Pressley As 'Claudine Jasper' In PURPOSE

Pressley steps into the role of Claudine Jasper beginning July 15. Porter and Wallace Meet the Press Ahead of CABARET Run

They began performances on Tuesday, July 22 and continue for the production’s final 13 weeks through Sunday, October 19.

Porter and Wallace Meet the Press Ahead of CABARET Run

They began performances on Tuesday, July 22 and continue for the production’s final 13 weeks through Sunday, October 19. Frankie Grande Visits STRANGER THINGS: THE FIRST SHADOW

He saw the show two days in a row this week, bringing his mother Joan to the show to meet the cast as well.

Frankie Grande Visits STRANGER THINGS: THE FIRST SHADOW

He saw the show two days in a row this week, bringing his mother Joan to the show to meet the cast as well. On the Opening Night Red Carpet for GINGER TWINSIES

Ginger Twinsies is running off-Broadway at the Orpheum Theatre.

On the Opening Night Red Carpet for GINGER TWINSIES

Ginger Twinsies is running off-Broadway at the Orpheum Theatre. First Look at ROLLING THUNDER Off-Broadway

Rolling Thunder will open July 24 at New World Stages.

First Look at ROLLING THUNDER Off-Broadway

Rolling Thunder will open July 24 at New World Stages. A PLAY ABOUT DAVID MAMET... Reading

Directed by Leslye Headland, the four-person cast featured Abbi Jacobson, Heléne Yorke, Billy Eichner and Paige Gilbert.

A PLAY ABOUT DAVID MAMET... Reading

Directed by Leslye Headland, the four-person cast featured Abbi Jacobson, Heléne Yorke, Billy Eichner and Paige Gilbert. Porter and Wallace Meet the Press Ahead of CABARET Run

They began performances on Tuesday, July 22 and continue for the production’s final 13 weeks through Sunday, October 19.

Porter and Wallace Meet the Press Ahead of CABARET Run

They began performances on Tuesday, July 22 and continue for the production’s final 13 weeks through Sunday, October 19. Frankie Grande Visits STRANGER THINGS: THE FIRST SHADOW

He saw the show two days in a row this week, bringing his mother Joan to the show to meet the cast as well.

Frankie Grande Visits STRANGER THINGS: THE FIRST SHADOW

He saw the show two days in a row this week, bringing his mother Joan to the show to meet the cast as well. On the Opening Night Red Carpet for GINGER TWINSIES

Ginger Twinsies is running off-Broadway at the Orpheum Theatre.

On the Opening Night Red Carpet for GINGER TWINSIES

Ginger Twinsies is running off-Broadway at the Orpheum Theatre. First Look at ROLLING THUNDER Off-Broadway

Rolling Thunder will open July 24 at New World Stages.

First Look at ROLLING THUNDER Off-Broadway

Rolling Thunder will open July 24 at New World Stages. A PLAY ABOUT DAVID MAMET... Reading

Directed by Leslye Headland, the four-person cast featured Abbi Jacobson, Heléne Yorke, Billy Eichner and Paige Gilbert.

A PLAY ABOUT DAVID MAMET... Reading

Directed by Leslye Headland, the four-person cast featured Abbi Jacobson, Heléne Yorke, Billy Eichner and Paige Gilbert. Broadway's Carole Demas Makes Solo Cabaret Debut in FIREFLY at 54 Below

The unforgettable show, celebrating the star's long Broadway and TV career, returns 9/6

Broadway's Carole Demas Makes Solo Cabaret Debut in FIREFLY at 54 Below

The unforgettable show, celebrating the star's long Broadway and TV career, returns 9/6 Frankie Grande Visits STRANGER THINGS: THE FIRST SHADOW

He saw the show two days in a row this week, bringing his mother Joan to the show to meet the cast as well.

Frankie Grande Visits STRANGER THINGS: THE FIRST SHADOW

He saw the show two days in a row this week, bringing his mother Joan to the show to meet the cast as well. On the Opening Night Red Carpet for GINGER TWINSIES

Ginger Twinsies is running off-Broadway at the Orpheum Theatre.

On the Opening Night Red Carpet for GINGER TWINSIES

Ginger Twinsies is running off-Broadway at the Orpheum Theatre. First Look at ROLLING THUNDER Off-Broadway

Rolling Thunder will open July 24 at New World Stages.

First Look at ROLLING THUNDER Off-Broadway

Rolling Thunder will open July 24 at New World Stages. A PLAY ABOUT DAVID MAMET... Reading

Directed by Leslye Headland, the four-person cast featured Abbi Jacobson, Heléne Yorke, Billy Eichner and Paige Gilbert.

A PLAY ABOUT DAVID MAMET... Reading

Directed by Leslye Headland, the four-person cast featured Abbi Jacobson, Heléne Yorke, Billy Eichner and Paige Gilbert. Broadway's Carole Demas Makes Solo Cabaret Debut in FIREFLY at 54 Below

The unforgettable show, celebrating the star's long Broadway and TV career, returns 9/6

Broadway's Carole Demas Makes Solo Cabaret Debut in FIREFLY at 54 Below

The unforgettable show, celebrating the star's long Broadway and TV career, returns 9/6 GINGER TWINSIES Company Celebrates Opening Night

Ginger Twinsies is running off-Broadway at the Orpheum Theatre.

GINGER TWINSIES Company Celebrates Opening Night

Ginger Twinsies is running off-Broadway at the Orpheum Theatre. On the Opening Night Red Carpet for GINGER TWINSIES

Ginger Twinsies is running off-Broadway at the Orpheum Theatre.

On the Opening Night Red Carpet for GINGER TWINSIES

Ginger Twinsies is running off-Broadway at the Orpheum Theatre. First Look at ROLLING THUNDER Off-Broadway

Rolling Thunder will open July 24 at New World Stages.

First Look at ROLLING THUNDER Off-Broadway

Rolling Thunder will open July 24 at New World Stages. A PLAY ABOUT DAVID MAMET... Reading

Directed by Leslye Headland, the four-person cast featured Abbi Jacobson, Heléne Yorke, Billy Eichner and Paige Gilbert.

A PLAY ABOUT DAVID MAMET... Reading

Directed by Leslye Headland, the four-person cast featured Abbi Jacobson, Heléne Yorke, Billy Eichner and Paige Gilbert. Broadway's Carole Demas Makes Solo Cabaret Debut in FIREFLY at 54 Below

The unforgettable show, celebrating the star's long Broadway and TV career, returns 9/6

Broadway's Carole Demas Makes Solo Cabaret Debut in FIREFLY at 54 Below

The unforgettable show, celebrating the star's long Broadway and TV career, returns 9/6 GINGER TWINSIES Company Celebrates Opening Night

Ginger Twinsies is running off-Broadway at the Orpheum Theatre.

GINGER TWINSIES Company Celebrates Opening Night

Ginger Twinsies is running off-Broadway at the Orpheum Theatre. Inside Barrington Stage's Gala A NIGHT ON THE RED CARPET

The event was held on Monday, July 21.

Inside Barrington Stage's Gala A NIGHT ON THE RED CARPET

The event was held on Monday, July 21. First Look at ROLLING THUNDER Off-Broadway

Rolling Thunder will open July 24 at New World Stages.

First Look at ROLLING THUNDER Off-Broadway

Rolling Thunder will open July 24 at New World Stages. A PLAY ABOUT DAVID MAMET... Reading

Directed by Leslye Headland, the four-person cast featured Abbi Jacobson, Heléne Yorke, Billy Eichner and Paige Gilbert.

A PLAY ABOUT DAVID MAMET... Reading

Directed by Leslye Headland, the four-person cast featured Abbi Jacobson, Heléne Yorke, Billy Eichner and Paige Gilbert. Broadway's Carole Demas Makes Solo Cabaret Debut in FIREFLY at 54 Below

The unforgettable show, celebrating the star's long Broadway and TV career, returns 9/6

Broadway's Carole Demas Makes Solo Cabaret Debut in FIREFLY at 54 Below

The unforgettable show, celebrating the star's long Broadway and TV career, returns 9/6 GINGER TWINSIES Company Celebrates Opening Night

Ginger Twinsies is running off-Broadway at the Orpheum Theatre.

GINGER TWINSIES Company Celebrates Opening Night

Ginger Twinsies is running off-Broadway at the Orpheum Theatre. Inside Barrington Stage's Gala A NIGHT ON THE RED CARPET

The event was held on Monday, July 21.

Inside Barrington Stage's Gala A NIGHT ON THE RED CARPET

The event was held on Monday, July 21. SPRING AWAKENING at Chance Theater

Spring Awakening will run through August 10 at Chance Theater

SPRING AWAKENING at Chance Theater

Spring Awakening will run through August 10 at Chance Theater A PLAY ABOUT DAVID MAMET... Reading

Directed by Leslye Headland, the four-person cast featured Abbi Jacobson, Heléne Yorke, Billy Eichner and Paige Gilbert.

A PLAY ABOUT DAVID MAMET... Reading

Directed by Leslye Headland, the four-person cast featured Abbi Jacobson, Heléne Yorke, Billy Eichner and Paige Gilbert. Broadway's Carole Demas Makes Solo Cabaret Debut in FIREFLY at 54 Below

The unforgettable show, celebrating the star's long Broadway and TV career, returns 9/6

Broadway's Carole Demas Makes Solo Cabaret Debut in FIREFLY at 54 Below

The unforgettable show, celebrating the star's long Broadway and TV career, returns 9/6 GINGER TWINSIES Company Celebrates Opening Night

Ginger Twinsies is running off-Broadway at the Orpheum Theatre.

GINGER TWINSIES Company Celebrates Opening Night

Ginger Twinsies is running off-Broadway at the Orpheum Theatre. Inside Barrington Stage's Gala A NIGHT ON THE RED CARPET

The event was held on Monday, July 21.

Inside Barrington Stage's Gala A NIGHT ON THE RED CARPET

The event was held on Monday, July 21. SPRING AWAKENING at Chance Theater

Spring Awakening will run through August 10 at Chance Theater

SPRING AWAKENING at Chance Theater

Spring Awakening will run through August 10 at Chance Theater Photo: First Look at DOLLY: A TRUE ORIGINAL MUSICAL

Get a First look at Carrie St. Louis as ‘Dolly,’ Katie Rose Clarke as ‘Dolly Parton,’ and Quinn Titcomb as ‘Little Dolly.’

Photo: First Look at DOLLY: A TRUE ORIGINAL MUSICAL

Get a First look at Carrie St. Louis as ‘Dolly,’ Katie Rose Clarke as ‘Dolly Parton,’ and Quinn Titcomb as ‘Little Dolly.’ Broadway's Carole Demas Makes Solo Cabaret Debut in FIREFLY at 54 Below

The unforgettable show, celebrating the star's long Broadway and TV career, returns 9/6

Broadway's Carole Demas Makes Solo Cabaret Debut in FIREFLY at 54 Below

The unforgettable show, celebrating the star's long Broadway and TV career, returns 9/6 GINGER TWINSIES Company Celebrates Opening Night

Ginger Twinsies is running off-Broadway at the Orpheum Theatre.

GINGER TWINSIES Company Celebrates Opening Night

Ginger Twinsies is running off-Broadway at the Orpheum Theatre. Inside Barrington Stage's Gala A NIGHT ON THE RED CARPET

The event was held on Monday, July 21.

Inside Barrington Stage's Gala A NIGHT ON THE RED CARPET

The event was held on Monday, July 21. SPRING AWAKENING at Chance Theater

Spring Awakening will run through August 10 at Chance Theater

SPRING AWAKENING at Chance Theater

Spring Awakening will run through August 10 at Chance Theater Photo: First Look at DOLLY: A TRUE ORIGINAL MUSICAL

Get a First look at Carrie St. Louis as ‘Dolly,’ Katie Rose Clarke as ‘Dolly Parton,’ and Quinn Titcomb as ‘Little Dolly.’

Photo: First Look at DOLLY: A TRUE ORIGINAL MUSICAL

Get a First look at Carrie St. Louis as ‘Dolly,’ Katie Rose Clarke as ‘Dolly Parton,’ and Quinn Titcomb as ‘Little Dolly.’ First Look at EVITA at The Muny

Performances run July 18-24.

First Look at EVITA at The Muny

Performances run July 18-24. GINGER TWINSIES Company Celebrates Opening Night

Ginger Twinsies is running off-Broadway at the Orpheum Theatre.

GINGER TWINSIES Company Celebrates Opening Night

Ginger Twinsies is running off-Broadway at the Orpheum Theatre. Inside Barrington Stage's Gala A NIGHT ON THE RED CARPET

The event was held on Monday, July 21.

Inside Barrington Stage's Gala A NIGHT ON THE RED CARPET

The event was held on Monday, July 21. SPRING AWAKENING at Chance Theater

Spring Awakening will run through August 10 at Chance Theater

SPRING AWAKENING at Chance Theater

Spring Awakening will run through August 10 at Chance Theater Photo: First Look at DOLLY: A TRUE ORIGINAL MUSICAL

Get a First look at Carrie St. Louis as ‘Dolly,’ Katie Rose Clarke as ‘Dolly Parton,’ and Quinn Titcomb as ‘Little Dolly.’

Photo: First Look at DOLLY: A TRUE ORIGINAL MUSICAL

Get a First look at Carrie St. Louis as ‘Dolly,’ Katie Rose Clarke as ‘Dolly Parton,’ and Quinn Titcomb as ‘Little Dolly.’ First Look at EVITA at The Muny

Performances run July 18-24.

First Look at EVITA at The Muny

Performances run July 18-24. Scherzinger and the Cast of SUNSET BLVD. Take Final Bow

The show played its final performance on July 20 at the St. James Theatre following 20 previews and 312 regular performances.

Scherzinger and the Cast of SUNSET BLVD. Take Final Bow

The show played its final performance on July 20 at the St. James Theatre following 20 previews and 312 regular performances. Inside Barrington Stage's Gala A NIGHT ON THE RED CARPET

The event was held on Monday, July 21.

Inside Barrington Stage's Gala A NIGHT ON THE RED CARPET

The event was held on Monday, July 21. SPRING AWAKENING at Chance Theater

Spring Awakening will run through August 10 at Chance Theater

SPRING AWAKENING at Chance Theater

Spring Awakening will run through August 10 at Chance Theater Photo: First Look at DOLLY: A TRUE ORIGINAL MUSICAL

Get a First look at Carrie St. Louis as ‘Dolly,’ Katie Rose Clarke as ‘Dolly Parton,’ and Quinn Titcomb as ‘Little Dolly.’

Photo: First Look at DOLLY: A TRUE ORIGINAL MUSICAL

Get a First look at Carrie St. Louis as ‘Dolly,’ Katie Rose Clarke as ‘Dolly Parton,’ and Quinn Titcomb as ‘Little Dolly.’ First Look at EVITA at The Muny

Performances run July 18-24.

First Look at EVITA at The Muny

Performances run July 18-24. Scherzinger and the Cast of SUNSET BLVD. Take Final Bow

The show played its final performance on July 20 at the St. James Theatre following 20 previews and 312 regular performances.

Scherzinger and the Cast of SUNSET BLVD. Take Final Bow

The show played its final performance on July 20 at the St. James Theatre following 20 previews and 312 regular performances. Billy Porter and Marisha Wallace in CABARET

Porter and Wallace begin performances on Tuesday, July 22.

Billy Porter and Marisha Wallace in CABARET

Porter and Wallace begin performances on Tuesday, July 22. SPRING AWAKENING at Chance Theater

Spring Awakening will run through August 10 at Chance Theater

SPRING AWAKENING at Chance Theater

Spring Awakening will run through August 10 at Chance Theater Photo: First Look at DOLLY: A TRUE ORIGINAL MUSICAL

Get a First look at Carrie St. Louis as ‘Dolly,’ Katie Rose Clarke as ‘Dolly Parton,’ and Quinn Titcomb as ‘Little Dolly.’

Photo: First Look at DOLLY: A TRUE ORIGINAL MUSICAL

Get a First look at Carrie St. Louis as ‘Dolly,’ Katie Rose Clarke as ‘Dolly Parton,’ and Quinn Titcomb as ‘Little Dolly.’ First Look at EVITA at The Muny

Performances run July 18-24.

First Look at EVITA at The Muny

Performances run July 18-24. Scherzinger and the Cast of SUNSET BLVD. Take Final Bow

The show played its final performance on July 20 at the St. James Theatre following 20 previews and 312 regular performances.

Scherzinger and the Cast of SUNSET BLVD. Take Final Bow

The show played its final performance on July 20 at the St. James Theatre following 20 previews and 312 regular performances. Billy Porter and Marisha Wallace in CABARET

Porter and Wallace begin performances on Tuesday, July 22.

Billy Porter and Marisha Wallace in CABARET

Porter and Wallace begin performances on Tuesday, July 22. The Hollywood Museum Opens Marx Brothers Exhibit LEGENDS OF LAUGHTER

Exhibit features rare memorabilia, original costumes, and family tributes to comedy legends.

The Hollywood Museum Opens Marx Brothers Exhibit LEGENDS OF LAUGHTER

Exhibit features rare memorabilia, original costumes, and family tributes to comedy legends.Industry

Get Broadway's #1 Newsletter

West End

EDINBURGH 2025: Hasan Al-Habib Q&A

Death to the West (Midlands) runs at Edfringe 30 July - 24 August

Death to the West (Midlands) runs at Edfringe 30 July - 24 August

New York City

PHOTOS: NICOLE ZURAITIS Plays Dizzy’s Club

Husband Dan Pugach on drums, Idan Morim Guitar, Sam Weber bass.

Husband Dan Pugach on drums, Idan Morim Guitar, Sam Weber bass.

United States

BWW Q&A: Billy Harrigan Tighe on Waitress at THEATRE RALEIGH

The Broadway actor discusses the role, the rehearsal process, and what sets Theatre Raleigh apart.

The Broadway actor discusses the role, the rehearsal process, and what sets Theatre Raleigh apart.

International

LES MISERABLES 40th-Anniversary Concert Tour to Play Manila, January 2026

Public tickets for this highly anticipated run will be sold starting August 11 via TicketWorld.

Public tickets for this highly anticipated run will be sold starting August 11 via TicketWorld.

.jpg?format=auto&width=300)