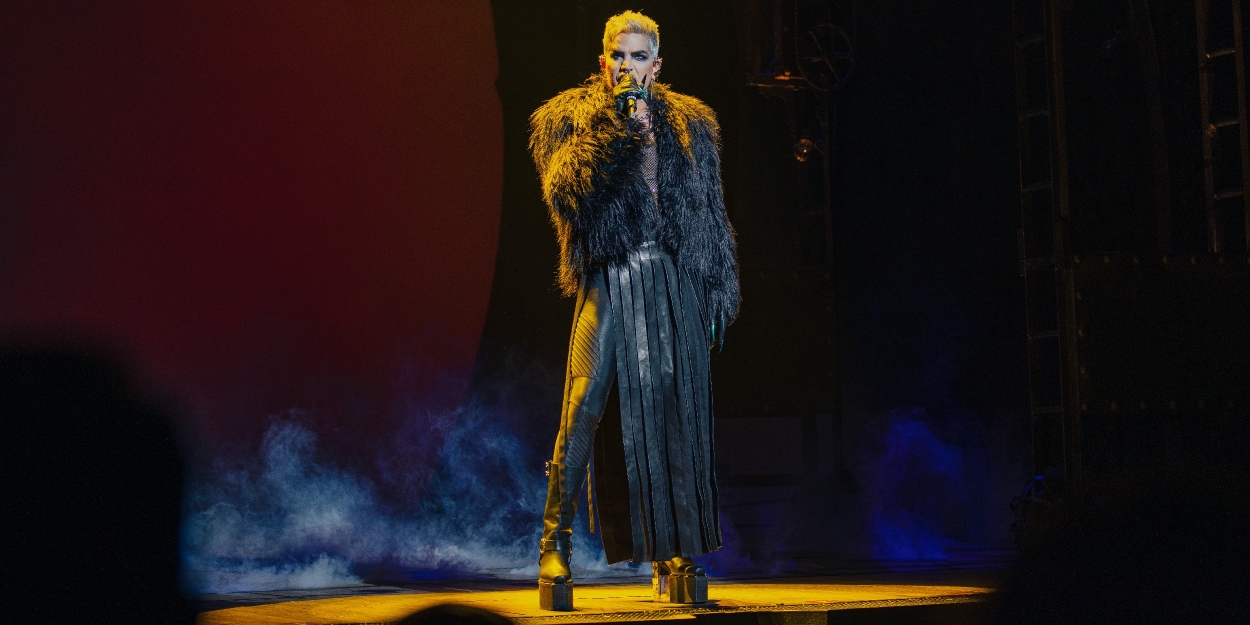

- Wake Up With BroadwayWorld August 4, 2025- Adam Lambert Sings JESUS CHRIST SUPERSTAR and More

- Zero to Hero: The Musical Evolution of Disney's HERCULES From Screen to Stage

- Exclusive: Oh My Pod U Guys- It's Gonna Be Great with Christopher Sieber

Latest News

Trending Stories

Recommended for You

The High Stakes of Broadway Recasting

A look back at recent major recastings in Broadway musicals. Did they pay off?

Kerry Butler, Alex Newell, Andrew Durand & More Join BAT BOY at New York City Center

Bat Boy will run October 29 through November 9, 2025 at New York City Center.

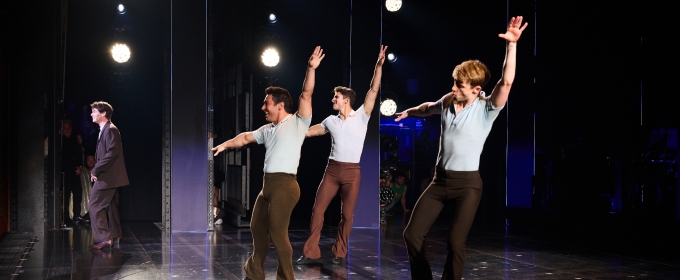

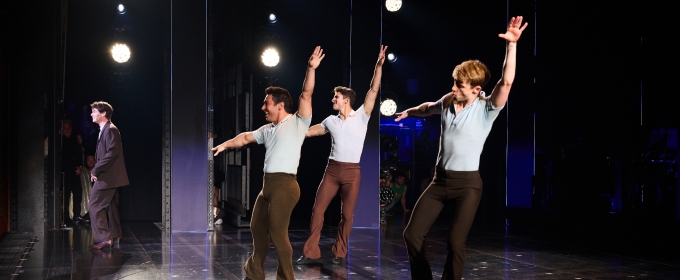

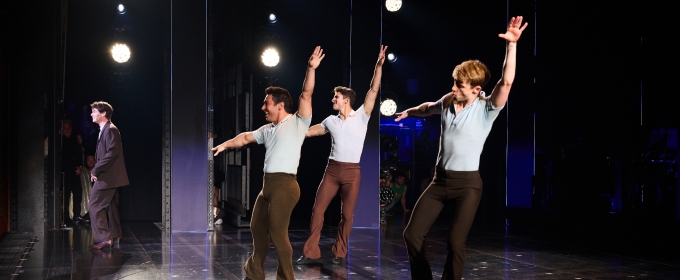

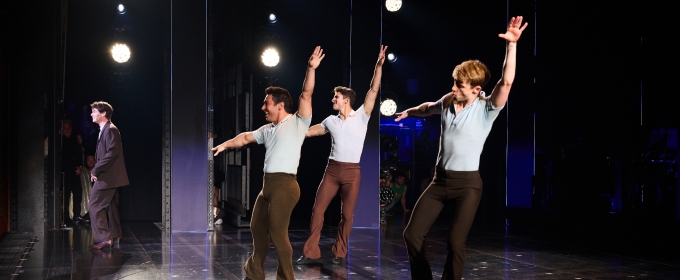

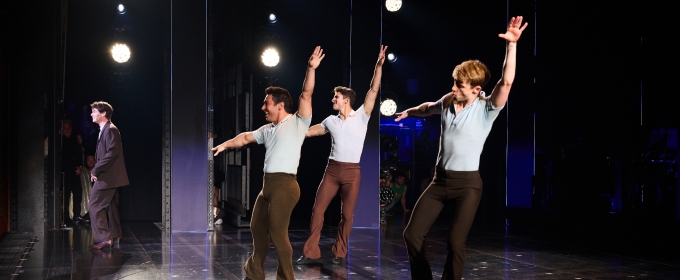

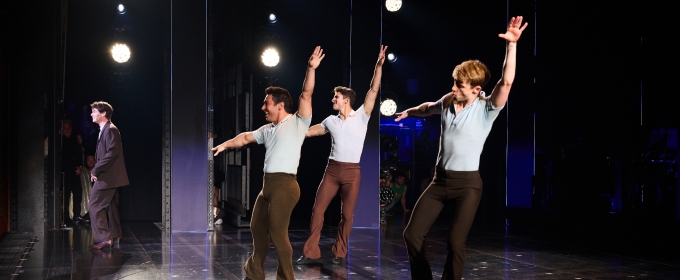

Photos: Inside A CHORUS LINE's 50th Anniversary Celebration

The event featured original stars Baayork Lee, Kelly Bishop, Wayne Cilento,

David Cromer Will Direct London Reading of GATSBY: AN AMERICAN MYTH

Further plans for the musical to be announced soon.

Ticket Central

Hot Photos this week

Inside A CHORUS LINE's 50th Anniversary Celebration

The event featured original stars Baayork Lee, Kelly Bishop, Wayne Cilento,

Inside A CHORUS LINE's 50th Anniversary Celebration

The event featured original stars Baayork Lee, Kelly Bishop, Wayne Cilento,

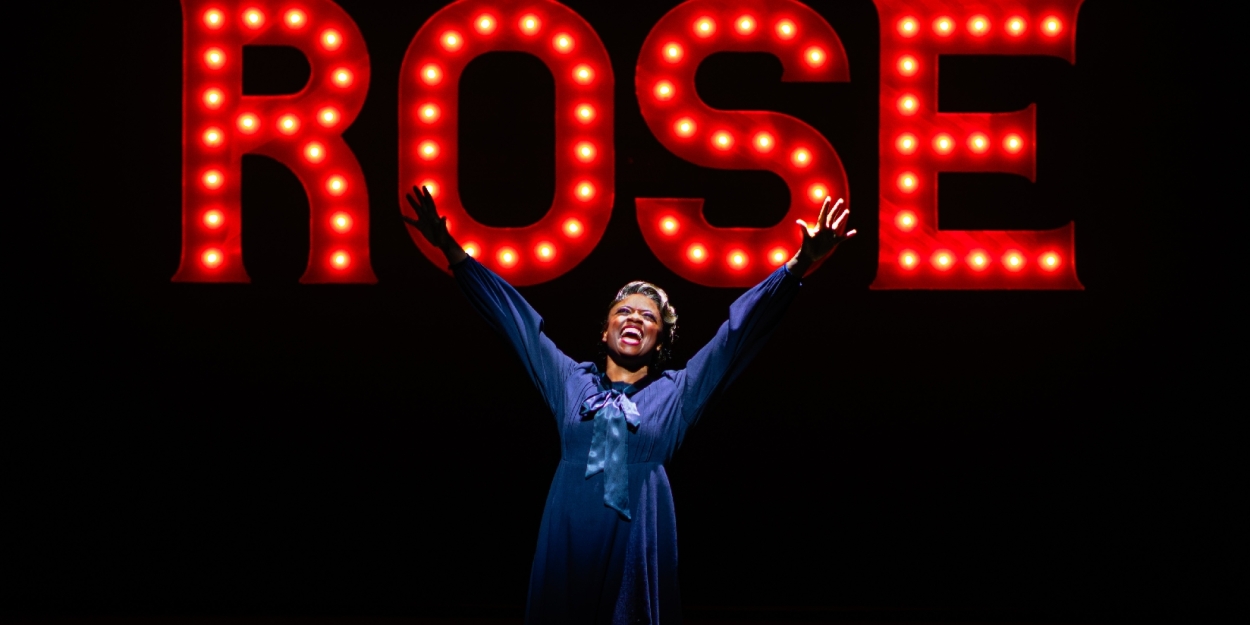

Scherzinger and the Cast of SUNSET BLVD. Take Final Bow

The show played its final performance on July 20 at the St. James Theatre following 20 previews and 312 regular performances.

Scherzinger and the Cast of SUNSET BLVD. Take Final Bow

The show played its final performance on July 20 at the St. James Theatre following 20 previews and 312 regular performances.

Robyn Hurder, Andrew Durand, and More Star in HIGH SOCIETY at Ogunquit Playhouse

The production runs July 24 through August 23 in Ogunquit, Maine.

Robyn Hurder, Andrew Durand, and More Star in HIGH SOCIETY at Ogunquit Playhouse

The production runs July 24 through August 23 in Ogunquit, Maine.

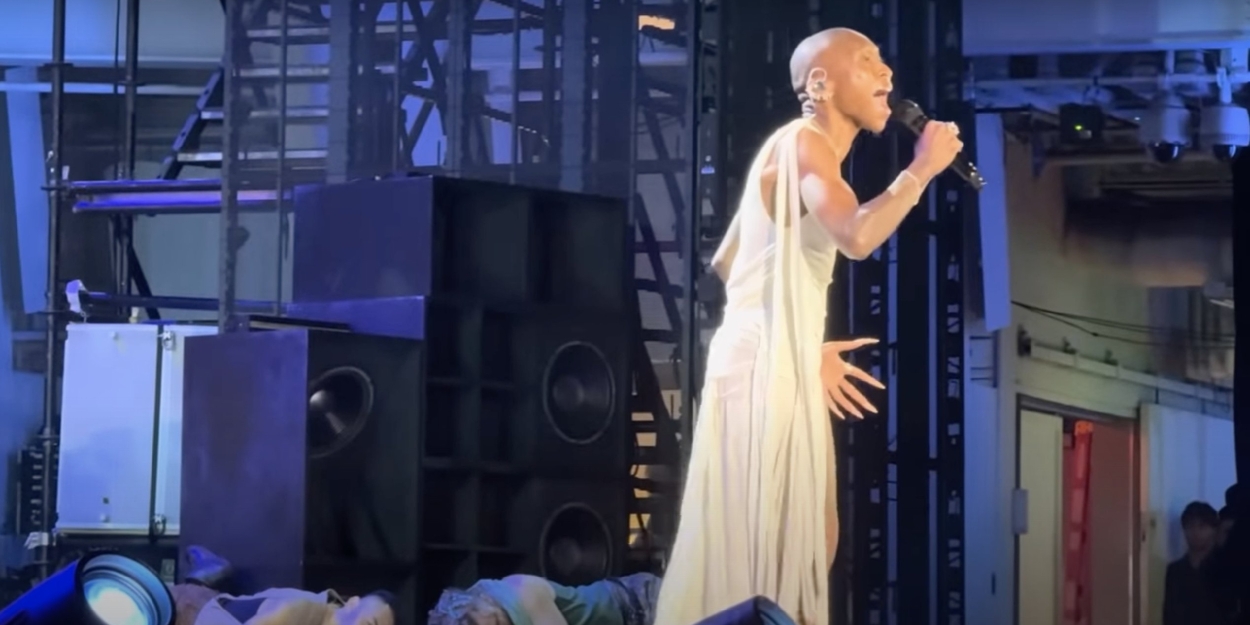

Billy Porter and Marisha Wallace in CABARET

Porter and Wallace begin performances on Tuesday, July 22.

Billy Porter and Marisha Wallace in CABARET

Porter and Wallace begin performances on Tuesday, July 22.

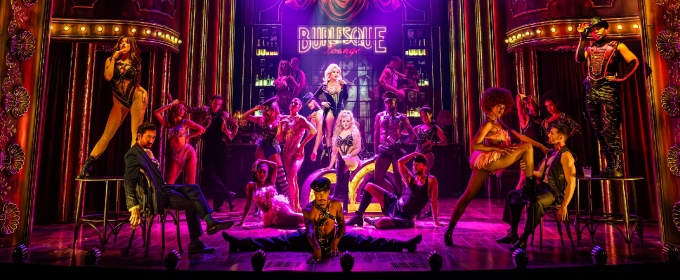

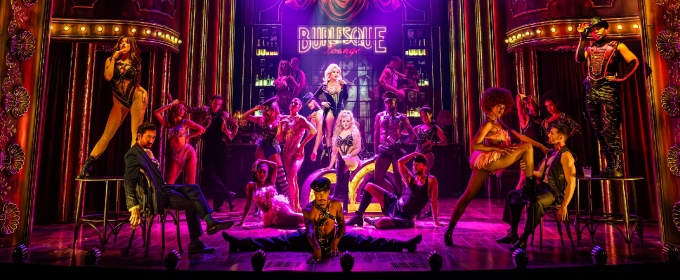

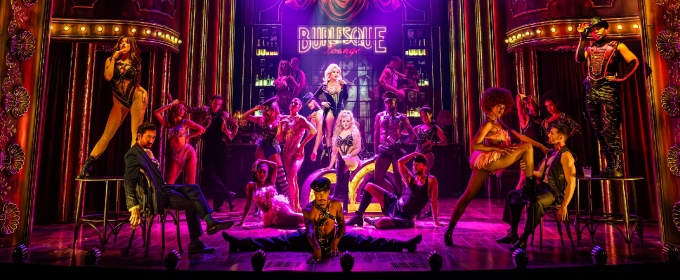

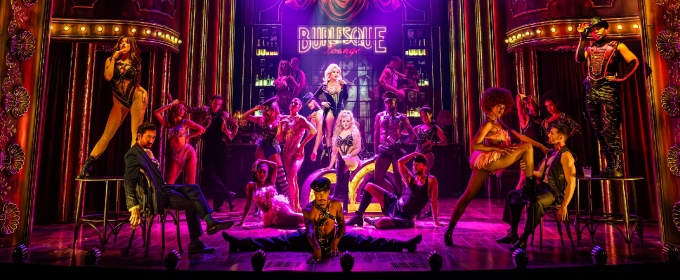

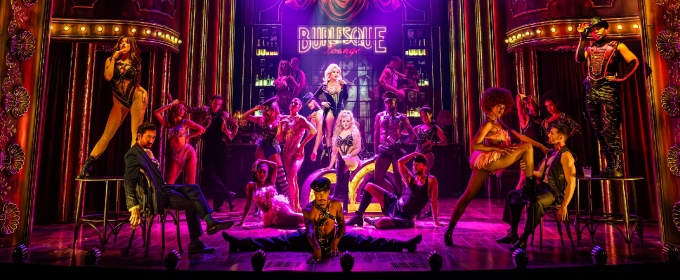

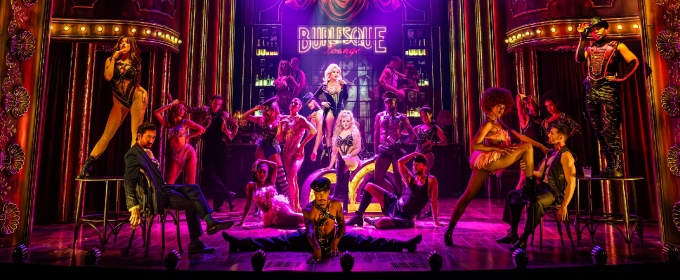

Jess Folley, Todrick Hall and More in BURLESQUE THE MUSICAL in London

The show plays for a limited season until Saturday 6 September 2025.

Jess Folley, Todrick Hall and More in BURLESQUE THE MUSICAL in London

The show plays for a limited season until Saturday 6 September 2025.

Cole Escola, Sadie Sink, and More at Opening Night of Josh Sharp's TA-DA!

Performances will continue for a limited run through August 23.

Cole Escola, Sadie Sink, and More at Opening Night of Josh Sharp's TA-DA!

Performances will continue for a limited run through August 23.

Scherzinger and the Cast of SUNSET BLVD. Take Final Bow

The show played its final performance on July 20 at the St. James Theatre following 20 previews and 312 regular performances.

Scherzinger and the Cast of SUNSET BLVD. Take Final Bow

The show played its final performance on July 20 at the St. James Theatre following 20 previews and 312 regular performances.

Robyn Hurder, Andrew Durand, and More Star in HIGH SOCIETY at Ogunquit Playhouse

The production runs July 24 through August 23 in Ogunquit, Maine.

Robyn Hurder, Andrew Durand, and More Star in HIGH SOCIETY at Ogunquit Playhouse

The production runs July 24 through August 23 in Ogunquit, Maine.

Billy Porter and Marisha Wallace in CABARET

Porter and Wallace begin performances on Tuesday, July 22.

Billy Porter and Marisha Wallace in CABARET

Porter and Wallace begin performances on Tuesday, July 22.

Jess Folley, Todrick Hall and More in BURLESQUE THE MUSICAL in London

The show plays for a limited season until Saturday 6 September 2025.

Jess Folley, Todrick Hall and More in BURLESQUE THE MUSICAL in London

The show plays for a limited season until Saturday 6 September 2025.

Cole Escola, Sadie Sink, and More at Opening Night of Josh Sharp's TA-DA!

Performances will continue for a limited run through August 23.

Cole Escola, Sadie Sink, and More at Opening Night of Josh Sharp's TA-DA!

Performances will continue for a limited run through August 23.

Taye Diggs and Wayne Brady in MOULIN ROUGE! THE MUSICAL

Taye Diggs plays through September 28, with Wayne Brady staying through November 9.

Taye Diggs and Wayne Brady in MOULIN ROUGE! THE MUSICAL

Taye Diggs plays through September 28, with Wayne Brady staying through November 9.

Robyn Hurder, Andrew Durand, and More Star in HIGH SOCIETY at Ogunquit Playhouse

The production runs July 24 through August 23 in Ogunquit, Maine.

Robyn Hurder, Andrew Durand, and More Star in HIGH SOCIETY at Ogunquit Playhouse

The production runs July 24 through August 23 in Ogunquit, Maine.

Billy Porter and Marisha Wallace in CABARET

Porter and Wallace begin performances on Tuesday, July 22.

Billy Porter and Marisha Wallace in CABARET

Porter and Wallace begin performances on Tuesday, July 22.

Jess Folley, Todrick Hall and More in BURLESQUE THE MUSICAL in London

The show plays for a limited season until Saturday 6 September 2025.

Jess Folley, Todrick Hall and More in BURLESQUE THE MUSICAL in London

The show plays for a limited season until Saturday 6 September 2025.

Cole Escola, Sadie Sink, and More at Opening Night of Josh Sharp's TA-DA!

Performances will continue for a limited run through August 23.

Cole Escola, Sadie Sink, and More at Opening Night of Josh Sharp's TA-DA!

Performances will continue for a limited run through August 23.

Taye Diggs and Wayne Brady in MOULIN ROUGE! THE MUSICAL

Taye Diggs plays through September 28, with Wayne Brady staying through November 9.

Taye Diggs and Wayne Brady in MOULIN ROUGE! THE MUSICAL

Taye Diggs plays through September 28, with Wayne Brady staying through November 9.

Wayne Brady and Taye Diggs Join the Cast of MOULIN ROUGE! THE MUSICAL

Diggs plays through September 28, with Brady staying through November 9.

Wayne Brady and Taye Diggs Join the Cast of MOULIN ROUGE! THE MUSICAL

Diggs plays through September 28, with Brady staying through November 9.

Billy Porter and Marisha Wallace in CABARET

Porter and Wallace begin performances on Tuesday, July 22.

Billy Porter and Marisha Wallace in CABARET

Porter and Wallace begin performances on Tuesday, July 22.

Jess Folley, Todrick Hall and More in BURLESQUE THE MUSICAL in London

The show plays for a limited season until Saturday 6 September 2025.

Jess Folley, Todrick Hall and More in BURLESQUE THE MUSICAL in London

The show plays for a limited season until Saturday 6 September 2025.

Cole Escola, Sadie Sink, and More at Opening Night of Josh Sharp's TA-DA!

Performances will continue for a limited run through August 23.

Cole Escola, Sadie Sink, and More at Opening Night of Josh Sharp's TA-DA!

Performances will continue for a limited run through August 23.

Taye Diggs and Wayne Brady in MOULIN ROUGE! THE MUSICAL

Taye Diggs plays through September 28, with Wayne Brady staying through November 9.

Taye Diggs and Wayne Brady in MOULIN ROUGE! THE MUSICAL

Taye Diggs plays through September 28, with Wayne Brady staying through November 9.

Wayne Brady and Taye Diggs Join the Cast of MOULIN ROUGE! THE MUSICAL

Diggs plays through September 28, with Brady staying through November 9.

Wayne Brady and Taye Diggs Join the Cast of MOULIN ROUGE! THE MUSICAL

Diggs plays through September 28, with Brady staying through November 9.

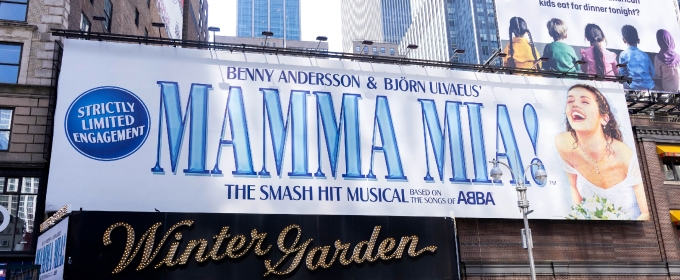

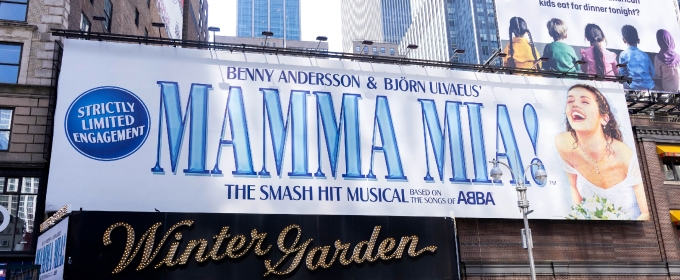

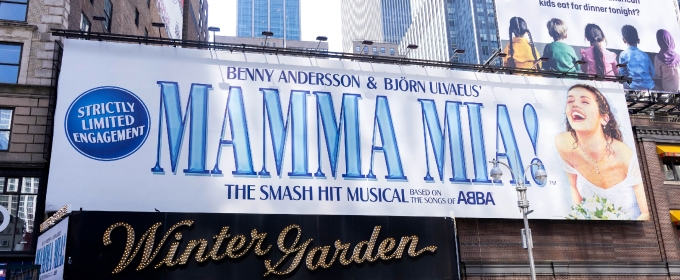

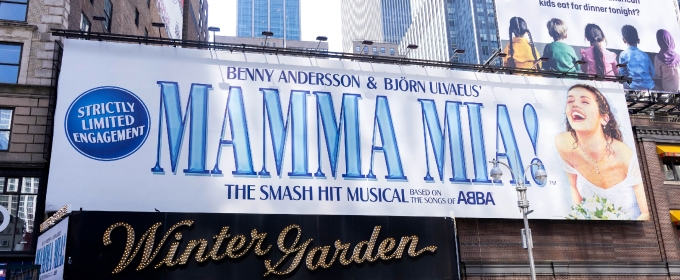

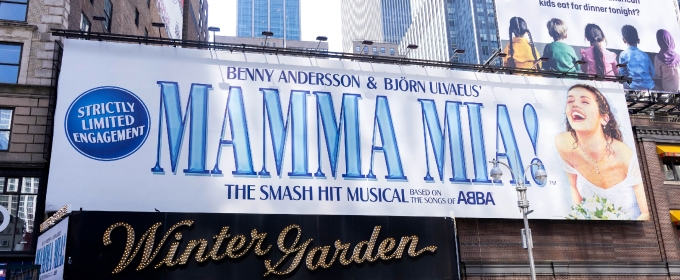

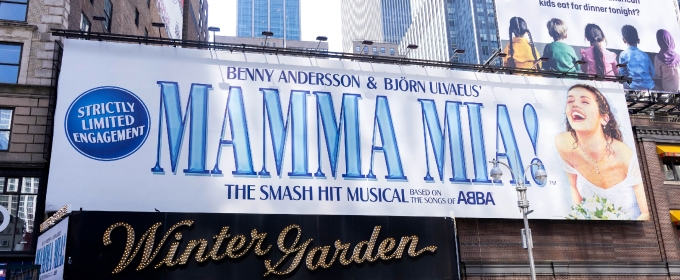

First Look at MAMMA MIA! as it Returns to Broadway

Performances begin this Saturday night, August 2 at the Winter Garden Theatre.

First Look at MAMMA MIA! as it Returns to Broadway

Performances begin this Saturday night, August 2 at the Winter Garden Theatre.

Jess Folley, Todrick Hall and More in BURLESQUE THE MUSICAL in London

The show plays for a limited season until Saturday 6 September 2025.

Jess Folley, Todrick Hall and More in BURLESQUE THE MUSICAL in London

The show plays for a limited season until Saturday 6 September 2025.

Cole Escola, Sadie Sink, and More at Opening Night of Josh Sharp's TA-DA!

Performances will continue for a limited run through August 23.

Cole Escola, Sadie Sink, and More at Opening Night of Josh Sharp's TA-DA!

Performances will continue for a limited run through August 23.

Taye Diggs and Wayne Brady in MOULIN ROUGE! THE MUSICAL

Taye Diggs plays through September 28, with Wayne Brady staying through November 9.

Taye Diggs and Wayne Brady in MOULIN ROUGE! THE MUSICAL

Taye Diggs plays through September 28, with Wayne Brady staying through November 9.

Wayne Brady and Taye Diggs Join the Cast of MOULIN ROUGE! THE MUSICAL

Diggs plays through September 28, with Brady staying through November 9.

Wayne Brady and Taye Diggs Join the Cast of MOULIN ROUGE! THE MUSICAL

Diggs plays through September 28, with Brady staying through November 9.

First Look at MAMMA MIA! as it Returns to Broadway

Performances begin this Saturday night, August 2 at the Winter Garden Theatre.

First Look at MAMMA MIA! as it Returns to Broadway

Performances begin this Saturday night, August 2 at the Winter Garden Theatre.

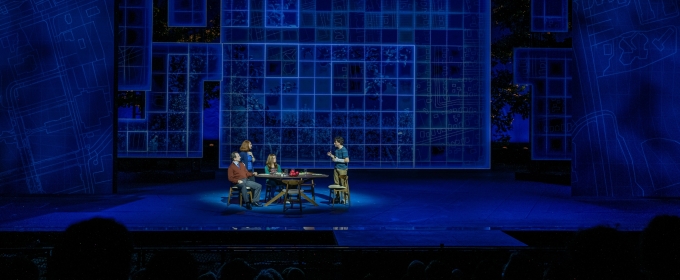

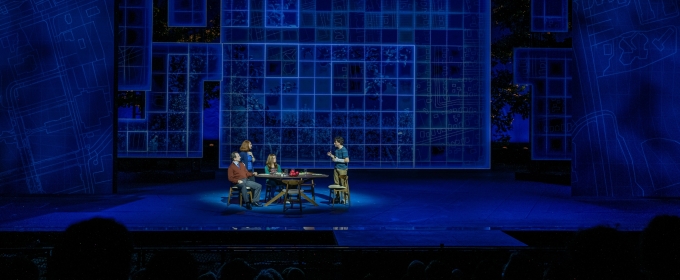

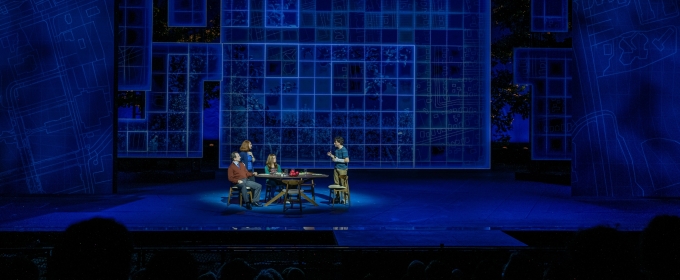

GINGER TWINSIES World Premiere First Look

Performances began on July 10, 2025, for the strictly limited, 16-week engagement through October 26, 2025.

GINGER TWINSIES World Premiere First Look

Performances began on July 10, 2025, for the strictly limited, 16-week engagement through October 26, 2025.

Cole Escola, Sadie Sink, and More at Opening Night of Josh Sharp's TA-DA!

Performances will continue for a limited run through August 23.

Cole Escola, Sadie Sink, and More at Opening Night of Josh Sharp's TA-DA!

Performances will continue for a limited run through August 23.

Taye Diggs and Wayne Brady in MOULIN ROUGE! THE MUSICAL

Taye Diggs plays through September 28, with Wayne Brady staying through November 9.

Taye Diggs and Wayne Brady in MOULIN ROUGE! THE MUSICAL

Taye Diggs plays through September 28, with Wayne Brady staying through November 9.

Wayne Brady and Taye Diggs Join the Cast of MOULIN ROUGE! THE MUSICAL

Diggs plays through September 28, with Brady staying through November 9.

Wayne Brady and Taye Diggs Join the Cast of MOULIN ROUGE! THE MUSICAL

Diggs plays through September 28, with Brady staying through November 9.

First Look at MAMMA MIA! as it Returns to Broadway

Performances begin this Saturday night, August 2 at the Winter Garden Theatre.

First Look at MAMMA MIA! as it Returns to Broadway

Performances begin this Saturday night, August 2 at the Winter Garden Theatre.

GINGER TWINSIES World Premiere First Look

Performances began on July 10, 2025, for the strictly limited, 16-week engagement through October 26, 2025.

GINGER TWINSIES World Premiere First Look

Performances began on July 10, 2025, for the strictly limited, 16-week engagement through October 26, 2025.

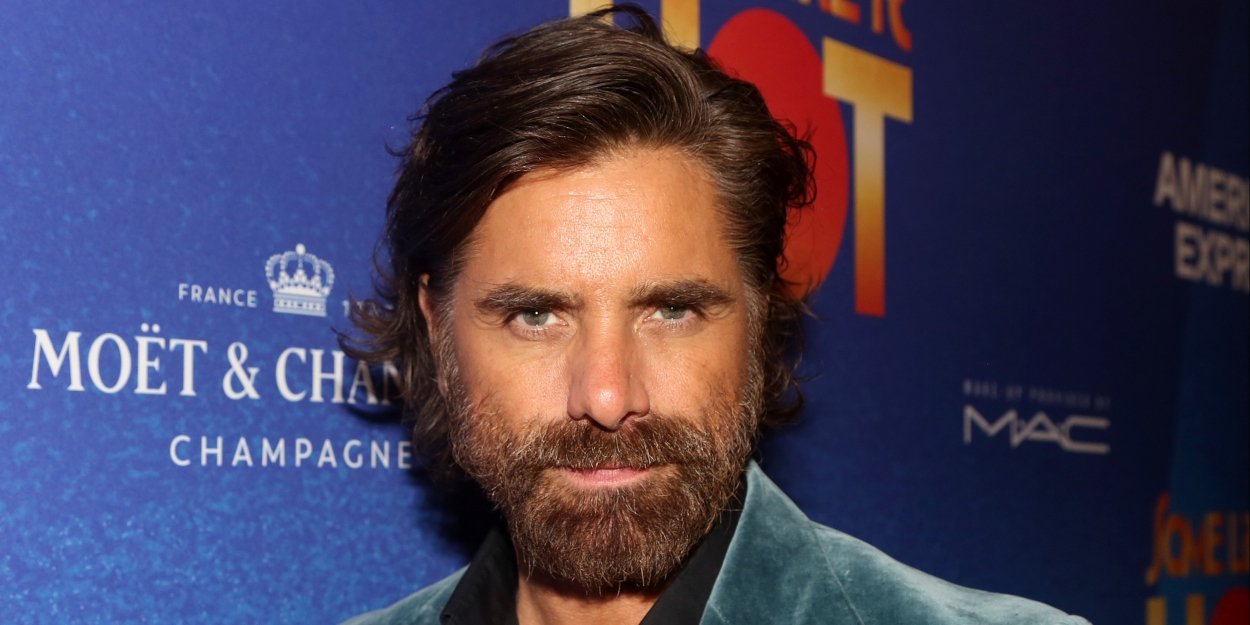

Inside Barrington Stage's Gala A NIGHT ON THE RED CARPET

The event was held on Monday, July 21.

Inside Barrington Stage's Gala A NIGHT ON THE RED CARPET

The event was held on Monday, July 21.

Taye Diggs and Wayne Brady in MOULIN ROUGE! THE MUSICAL

Taye Diggs plays through September 28, with Wayne Brady staying through November 9.

Taye Diggs and Wayne Brady in MOULIN ROUGE! THE MUSICAL

Taye Diggs plays through September 28, with Wayne Brady staying through November 9.

Wayne Brady and Taye Diggs Join the Cast of MOULIN ROUGE! THE MUSICAL

Diggs plays through September 28, with Brady staying through November 9.

Wayne Brady and Taye Diggs Join the Cast of MOULIN ROUGE! THE MUSICAL

Diggs plays through September 28, with Brady staying through November 9.

First Look at MAMMA MIA! as it Returns to Broadway

Performances begin this Saturday night, August 2 at the Winter Garden Theatre.

First Look at MAMMA MIA! as it Returns to Broadway

Performances begin this Saturday night, August 2 at the Winter Garden Theatre.

GINGER TWINSIES World Premiere First Look

Performances began on July 10, 2025, for the strictly limited, 16-week engagement through October 26, 2025.

GINGER TWINSIES World Premiere First Look

Performances began on July 10, 2025, for the strictly limited, 16-week engagement through October 26, 2025.

Inside Barrington Stage's Gala A NIGHT ON THE RED CARPET

The event was held on Monday, July 21.

Inside Barrington Stage's Gala A NIGHT ON THE RED CARPET

The event was held on Monday, July 21.

On the Red Carpet for A CHORUS LINE's 50th Anniversary

The event benefitted the Entertainment Community Fund’s programs serving dance professionals.

On the Red Carpet for A CHORUS LINE's 50th Anniversary

The event benefitted the Entertainment Community Fund’s programs serving dance professionals.

Wayne Brady and Taye Diggs Join the Cast of MOULIN ROUGE! THE MUSICAL

Diggs plays through September 28, with Brady staying through November 9.

Wayne Brady and Taye Diggs Join the Cast of MOULIN ROUGE! THE MUSICAL

Diggs plays through September 28, with Brady staying through November 9.

First Look at MAMMA MIA! as it Returns to Broadway

Performances begin this Saturday night, August 2 at the Winter Garden Theatre.

First Look at MAMMA MIA! as it Returns to Broadway

Performances begin this Saturday night, August 2 at the Winter Garden Theatre.

GINGER TWINSIES World Premiere First Look

Performances began on July 10, 2025, for the strictly limited, 16-week engagement through October 26, 2025.

GINGER TWINSIES World Premiere First Look

Performances began on July 10, 2025, for the strictly limited, 16-week engagement through October 26, 2025.

Inside Barrington Stage's Gala A NIGHT ON THE RED CARPET

The event was held on Monday, July 21.

Inside Barrington Stage's Gala A NIGHT ON THE RED CARPET

The event was held on Monday, July 21.

On the Red Carpet for A CHORUS LINE's 50th Anniversary

The event benefitted the Entertainment Community Fund’s programs serving dance professionals.

On the Red Carpet for A CHORUS LINE's 50th Anniversary

The event benefitted the Entertainment Community Fund’s programs serving dance professionals.

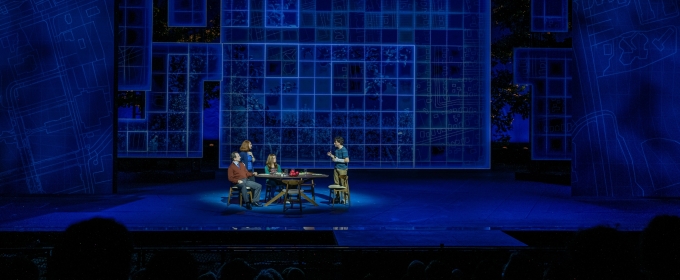

Michael Fabisch, Rob McClure, Jackie Burns and More in DEAR EVAN HANSEN at The Muny

The musical is now running through August 3.

Michael Fabisch, Rob McClure, Jackie Burns and More in DEAR EVAN HANSEN at The Muny

The musical is now running through August 3.

First Look at MAMMA MIA! as it Returns to Broadway

Performances begin this Saturday night, August 2 at the Winter Garden Theatre.

First Look at MAMMA MIA! as it Returns to Broadway

Performances begin this Saturday night, August 2 at the Winter Garden Theatre.

GINGER TWINSIES World Premiere First Look

Performances began on July 10, 2025, for the strictly limited, 16-week engagement through October 26, 2025.

GINGER TWINSIES World Premiere First Look

Performances began on July 10, 2025, for the strictly limited, 16-week engagement through October 26, 2025.

Inside Barrington Stage's Gala A NIGHT ON THE RED CARPET

The event was held on Monday, July 21.

Inside Barrington Stage's Gala A NIGHT ON THE RED CARPET

The event was held on Monday, July 21.

On the Red Carpet for A CHORUS LINE's 50th Anniversary

The event benefitted the Entertainment Community Fund’s programs serving dance professionals.

On the Red Carpet for A CHORUS LINE's 50th Anniversary

The event benefitted the Entertainment Community Fund’s programs serving dance professionals.

Michael Fabisch, Rob McClure, Jackie Burns and More in DEAR EVAN HANSEN at The Muny

The musical is now running through August 3.

Michael Fabisch, Rob McClure, Jackie Burns and More in DEAR EVAN HANSEN at The Muny

The musical is now running through August 3.

GINGER TWINSIES Celebrates Its Star-Studded Opening Night

The cast was joined by many familiar faces including Jesse Tyler Ferguson, Lin-Manuel Miranda, Busy Phillips, and more.

GINGER TWINSIES Celebrates Its Star-Studded Opening Night

The cast was joined by many familiar faces including Jesse Tyler Ferguson, Lin-Manuel Miranda, Busy Phillips, and more.

GINGER TWINSIES World Premiere First Look

Performances began on July 10, 2025, for the strictly limited, 16-week engagement through October 26, 2025.

GINGER TWINSIES World Premiere First Look

Performances began on July 10, 2025, for the strictly limited, 16-week engagement through October 26, 2025.

Inside Barrington Stage's Gala A NIGHT ON THE RED CARPET

The event was held on Monday, July 21.

Inside Barrington Stage's Gala A NIGHT ON THE RED CARPET

The event was held on Monday, July 21.

On the Red Carpet for A CHORUS LINE's 50th Anniversary

The event benefitted the Entertainment Community Fund’s programs serving dance professionals.

On the Red Carpet for A CHORUS LINE's 50th Anniversary

The event benefitted the Entertainment Community Fund’s programs serving dance professionals.

Michael Fabisch, Rob McClure, Jackie Burns and More in DEAR EVAN HANSEN at The Muny

The musical is now running through August 3.

Michael Fabisch, Rob McClure, Jackie Burns and More in DEAR EVAN HANSEN at The Muny

The musical is now running through August 3.

GINGER TWINSIES Celebrates Its Star-Studded Opening Night

The cast was joined by many familiar faces including Jesse Tyler Ferguson, Lin-Manuel Miranda, Busy Phillips, and more.

GINGER TWINSIES Celebrates Its Star-Studded Opening Night

The cast was joined by many familiar faces including Jesse Tyler Ferguson, Lin-Manuel Miranda, Busy Phillips, and more.

MAMMA MIA! Returns to the Winter Garden Theatre

The limited engagement will play for six months only, through Sunday, February 1, 2026.

MAMMA MIA! Returns to the Winter Garden Theatre

The limited engagement will play for six months only, through Sunday, February 1, 2026.

Inside Barrington Stage's Gala A NIGHT ON THE RED CARPET

The event was held on Monday, July 21.

Inside Barrington Stage's Gala A NIGHT ON THE RED CARPET

The event was held on Monday, July 21.

On the Red Carpet for A CHORUS LINE's 50th Anniversary

The event benefitted the Entertainment Community Fund’s programs serving dance professionals.

On the Red Carpet for A CHORUS LINE's 50th Anniversary

The event benefitted the Entertainment Community Fund’s programs serving dance professionals.

Michael Fabisch, Rob McClure, Jackie Burns and More in DEAR EVAN HANSEN at The Muny

The musical is now running through August 3.

Michael Fabisch, Rob McClure, Jackie Burns and More in DEAR EVAN HANSEN at The Muny

The musical is now running through August 3.

GINGER TWINSIES Celebrates Its Star-Studded Opening Night

The cast was joined by many familiar faces including Jesse Tyler Ferguson, Lin-Manuel Miranda, Busy Phillips, and more.

GINGER TWINSIES Celebrates Its Star-Studded Opening Night

The cast was joined by many familiar faces including Jesse Tyler Ferguson, Lin-Manuel Miranda, Busy Phillips, and more.

MAMMA MIA! Returns to the Winter Garden Theatre

The limited engagement will play for six months only, through Sunday, February 1, 2026.

MAMMA MIA! Returns to the Winter Garden Theatre

The limited engagement will play for six months only, through Sunday, February 1, 2026.

Princess of Thailand Visits HADESTOWN on Broadway

She attended the show to visit Hadestown cast member Myra Molloy, who plays Eurydice and is originally from Thailand. See photos here!

Princess of Thailand Visits HADESTOWN on Broadway

She attended the show to visit Hadestown cast member Myra Molloy, who plays Eurydice and is originally from Thailand. See photos here!

On the Red Carpet for A CHORUS LINE's 50th Anniversary

The event benefitted the Entertainment Community Fund’s programs serving dance professionals.

On the Red Carpet for A CHORUS LINE's 50th Anniversary

The event benefitted the Entertainment Community Fund’s programs serving dance professionals.

Michael Fabisch, Rob McClure, Jackie Burns and More in DEAR EVAN HANSEN at The Muny

The musical is now running through August 3.

Michael Fabisch, Rob McClure, Jackie Burns and More in DEAR EVAN HANSEN at The Muny

The musical is now running through August 3.

GINGER TWINSIES Celebrates Its Star-Studded Opening Night

The cast was joined by many familiar faces including Jesse Tyler Ferguson, Lin-Manuel Miranda, Busy Phillips, and more.

GINGER TWINSIES Celebrates Its Star-Studded Opening Night

The cast was joined by many familiar faces including Jesse Tyler Ferguson, Lin-Manuel Miranda, Busy Phillips, and more.

MAMMA MIA! Returns to the Winter Garden Theatre

The limited engagement will play for six months only, through Sunday, February 1, 2026.

MAMMA MIA! Returns to the Winter Garden Theatre

The limited engagement will play for six months only, through Sunday, February 1, 2026.

Princess of Thailand Visits HADESTOWN on Broadway

She attended the show to visit Hadestown cast member Myra Molloy, who plays Eurydice and is originally from Thailand. See photos here!

Princess of Thailand Visits HADESTOWN on Broadway

She attended the show to visit Hadestown cast member Myra Molloy, who plays Eurydice and is originally from Thailand. See photos here!

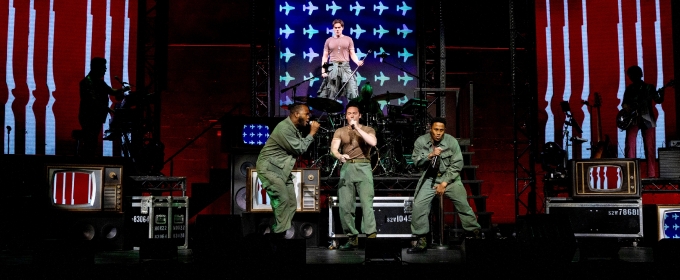

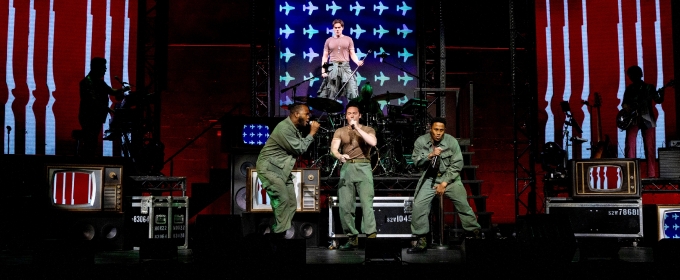

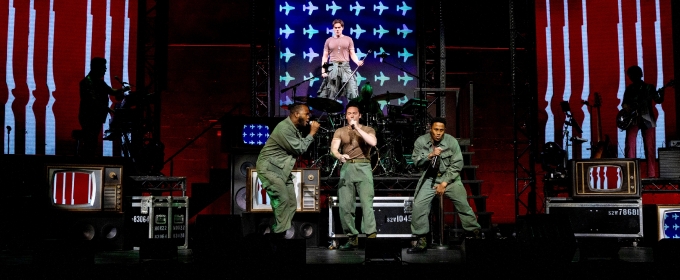

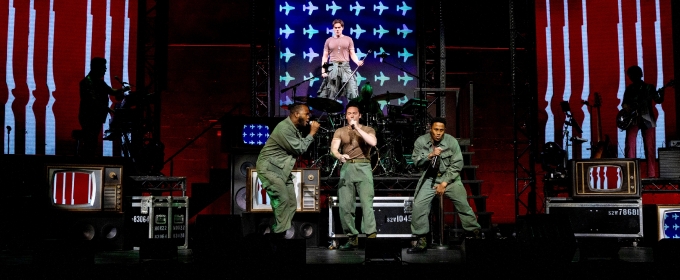

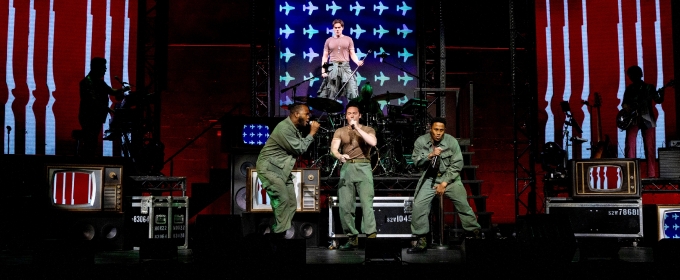

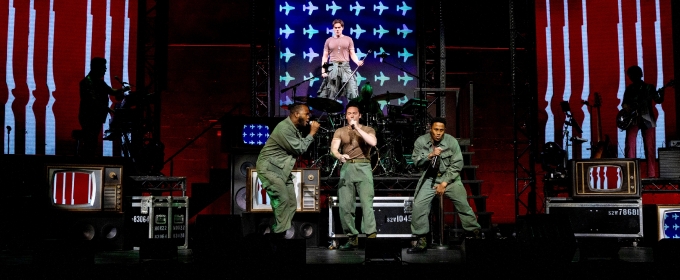

First Look at ROLLING THUNDER Off-Broadway

Rolling Thunder will open July 24 at New World Stages.

First Look at ROLLING THUNDER Off-Broadway

Rolling Thunder will open July 24 at New World Stages.

Michael Fabisch, Rob McClure, Jackie Burns and More in DEAR EVAN HANSEN at The Muny

The musical is now running through August 3.

Michael Fabisch, Rob McClure, Jackie Burns and More in DEAR EVAN HANSEN at The Muny

The musical is now running through August 3.

GINGER TWINSIES Celebrates Its Star-Studded Opening Night

The cast was joined by many familiar faces including Jesse Tyler Ferguson, Lin-Manuel Miranda, Busy Phillips, and more.

GINGER TWINSIES Celebrates Its Star-Studded Opening Night

The cast was joined by many familiar faces including Jesse Tyler Ferguson, Lin-Manuel Miranda, Busy Phillips, and more.

MAMMA MIA! Returns to the Winter Garden Theatre

The limited engagement will play for six months only, through Sunday, February 1, 2026.

MAMMA MIA! Returns to the Winter Garden Theatre

The limited engagement will play for six months only, through Sunday, February 1, 2026.

Princess of Thailand Visits HADESTOWN on Broadway

She attended the show to visit Hadestown cast member Myra Molloy, who plays Eurydice and is originally from Thailand. See photos here!

Princess of Thailand Visits HADESTOWN on Broadway

She attended the show to visit Hadestown cast member Myra Molloy, who plays Eurydice and is originally from Thailand. See photos here!

First Look at ROLLING THUNDER Off-Broadway

Rolling Thunder will open July 24 at New World Stages.

First Look at ROLLING THUNDER Off-Broadway

Rolling Thunder will open July 24 at New World Stages.

Porter and Wallace Meet the Press Ahead of CABARET Run

They began performances on Tuesday, July 22 and continue for the production’s final 13 weeks through Sunday, October 19.

Porter and Wallace Meet the Press Ahead of CABARET Run

They began performances on Tuesday, July 22 and continue for the production’s final 13 weeks through Sunday, October 19.

GINGER TWINSIES Celebrates Its Star-Studded Opening Night

The cast was joined by many familiar faces including Jesse Tyler Ferguson, Lin-Manuel Miranda, Busy Phillips, and more.

GINGER TWINSIES Celebrates Its Star-Studded Opening Night

The cast was joined by many familiar faces including Jesse Tyler Ferguson, Lin-Manuel Miranda, Busy Phillips, and more.

MAMMA MIA! Returns to the Winter Garden Theatre

The limited engagement will play for six months only, through Sunday, February 1, 2026.

MAMMA MIA! Returns to the Winter Garden Theatre

The limited engagement will play for six months only, through Sunday, February 1, 2026.

Princess of Thailand Visits HADESTOWN on Broadway

She attended the show to visit Hadestown cast member Myra Molloy, who plays Eurydice and is originally from Thailand. See photos here!

Princess of Thailand Visits HADESTOWN on Broadway

She attended the show to visit Hadestown cast member Myra Molloy, who plays Eurydice and is originally from Thailand. See photos here!

First Look at ROLLING THUNDER Off-Broadway

Rolling Thunder will open July 24 at New World Stages.

First Look at ROLLING THUNDER Off-Broadway

Rolling Thunder will open July 24 at New World Stages.

Porter and Wallace Meet the Press Ahead of CABARET Run

They began performances on Tuesday, July 22 and continue for the production’s final 13 weeks through Sunday, October 19.

Porter and Wallace Meet the Press Ahead of CABARET Run

They began performances on Tuesday, July 22 and continue for the production’s final 13 weeks through Sunday, October 19.

GINGER TWINSIES Company Celebrates Opening Night

Ginger Twinsies is running off-Broadway at the Orpheum Theatre.

GINGER TWINSIES Company Celebrates Opening Night

Ginger Twinsies is running off-Broadway at the Orpheum Theatre.

MAMMA MIA! Returns to the Winter Garden Theatre

The limited engagement will play for six months only, through Sunday, February 1, 2026.

MAMMA MIA! Returns to the Winter Garden Theatre

The limited engagement will play for six months only, through Sunday, February 1, 2026.

Princess of Thailand Visits HADESTOWN on Broadway

She attended the show to visit Hadestown cast member Myra Molloy, who plays Eurydice and is originally from Thailand. See photos here!

Princess of Thailand Visits HADESTOWN on Broadway

She attended the show to visit Hadestown cast member Myra Molloy, who plays Eurydice and is originally from Thailand. See photos here!

First Look at ROLLING THUNDER Off-Broadway

Rolling Thunder will open July 24 at New World Stages.

First Look at ROLLING THUNDER Off-Broadway

Rolling Thunder will open July 24 at New World Stages.

Porter and Wallace Meet the Press Ahead of CABARET Run

They began performances on Tuesday, July 22 and continue for the production’s final 13 weeks through Sunday, October 19.

Porter and Wallace Meet the Press Ahead of CABARET Run

They began performances on Tuesday, July 22 and continue for the production’s final 13 weeks through Sunday, October 19.

GINGER TWINSIES Company Celebrates Opening Night

Ginger Twinsies is running off-Broadway at the Orpheum Theatre.

GINGER TWINSIES Company Celebrates Opening Night

Ginger Twinsies is running off-Broadway at the Orpheum Theatre.

On the Opening Night Red Carpet for GINGER TWINSIES

Ginger Twinsies is running off-Broadway at the Orpheum Theatre.

On the Opening Night Red Carpet for GINGER TWINSIES

Ginger Twinsies is running off-Broadway at the Orpheum Theatre.

Princess of Thailand Visits HADESTOWN on Broadway

She attended the show to visit Hadestown cast member Myra Molloy, who plays Eurydice and is originally from Thailand. See photos here!

Princess of Thailand Visits HADESTOWN on Broadway

She attended the show to visit Hadestown cast member Myra Molloy, who plays Eurydice and is originally from Thailand. See photos here!

First Look at ROLLING THUNDER Off-Broadway

Rolling Thunder will open July 24 at New World Stages.

First Look at ROLLING THUNDER Off-Broadway

Rolling Thunder will open July 24 at New World Stages.

Porter and Wallace Meet the Press Ahead of CABARET Run

They began performances on Tuesday, July 22 and continue for the production’s final 13 weeks through Sunday, October 19.

Porter and Wallace Meet the Press Ahead of CABARET Run

They began performances on Tuesday, July 22 and continue for the production’s final 13 weeks through Sunday, October 19.

GINGER TWINSIES Company Celebrates Opening Night

Ginger Twinsies is running off-Broadway at the Orpheum Theatre.

GINGER TWINSIES Company Celebrates Opening Night

Ginger Twinsies is running off-Broadway at the Orpheum Theatre.

On the Opening Night Red Carpet for GINGER TWINSIES

Ginger Twinsies is running off-Broadway at the Orpheum Theatre.

On the Opening Night Red Carpet for GINGER TWINSIES

Ginger Twinsies is running off-Broadway at the Orpheum Theatre.

Frankie Grande Visits STRANGER THINGS: THE FIRST SHADOW

He saw the show two days in a row this week, bringing his mother Joan to the show to meet the cast as well.

Frankie Grande Visits STRANGER THINGS: THE FIRST SHADOW

He saw the show two days in a row this week, bringing his mother Joan to the show to meet the cast as well.

First Look at ROLLING THUNDER Off-Broadway

Rolling Thunder will open July 24 at New World Stages.

First Look at ROLLING THUNDER Off-Broadway

Rolling Thunder will open July 24 at New World Stages.

Porter and Wallace Meet the Press Ahead of CABARET Run

They began performances on Tuesday, July 22 and continue for the production’s final 13 weeks through Sunday, October 19.

Porter and Wallace Meet the Press Ahead of CABARET Run

They began performances on Tuesday, July 22 and continue for the production’s final 13 weeks through Sunday, October 19.

GINGER TWINSIES Company Celebrates Opening Night

Ginger Twinsies is running off-Broadway at the Orpheum Theatre.

GINGER TWINSIES Company Celebrates Opening Night

Ginger Twinsies is running off-Broadway at the Orpheum Theatre.

On the Opening Night Red Carpet for GINGER TWINSIES

Ginger Twinsies is running off-Broadway at the Orpheum Theatre.

On the Opening Night Red Carpet for GINGER TWINSIES

Ginger Twinsies is running off-Broadway at the Orpheum Theatre.

Frankie Grande Visits STRANGER THINGS: THE FIRST SHADOW

He saw the show two days in a row this week, bringing his mother Joan to the show to meet the cast as well.

Frankie Grande Visits STRANGER THINGS: THE FIRST SHADOW

He saw the show two days in a row this week, bringing his mother Joan to the show to meet the cast as well.

Review: 'JOSEPHINE' & 'PAGLIACCI' at Union Avenue Opera

runs through August 2

Review: 'JOSEPHINE' & 'PAGLIACCI' at Union Avenue Opera

runs through August 2

Porter and Wallace Meet the Press Ahead of CABARET Run

They began performances on Tuesday, July 22 and continue for the production’s final 13 weeks through Sunday, October 19.

Porter and Wallace Meet the Press Ahead of CABARET Run

They began performances on Tuesday, July 22 and continue for the production’s final 13 weeks through Sunday, October 19.

GINGER TWINSIES Company Celebrates Opening Night

Ginger Twinsies is running off-Broadway at the Orpheum Theatre.

GINGER TWINSIES Company Celebrates Opening Night

Ginger Twinsies is running off-Broadway at the Orpheum Theatre.

On the Opening Night Red Carpet for GINGER TWINSIES

Ginger Twinsies is running off-Broadway at the Orpheum Theatre.

On the Opening Night Red Carpet for GINGER TWINSIES

Ginger Twinsies is running off-Broadway at the Orpheum Theatre.

Frankie Grande Visits STRANGER THINGS: THE FIRST SHADOW

He saw the show two days in a row this week, bringing his mother Joan to the show to meet the cast as well.

Frankie Grande Visits STRANGER THINGS: THE FIRST SHADOW

He saw the show two days in a row this week, bringing his mother Joan to the show to meet the cast as well.

Review: 'JOSEPHINE' & 'PAGLIACCI' at Union Avenue Opera

runs through August 2

Review: 'JOSEPHINE' & 'PAGLIACCI' at Union Avenue Opera

runs through August 2

A PLAY ABOUT DAVID MAMET... Reading

Directed by Leslye Headland, the four-person cast featured Abbi Jacobson, Heléne Yorke, Billy Eichner and Paige Gilbert.

A PLAY ABOUT DAVID MAMET... Reading

Directed by Leslye Headland, the four-person cast featured Abbi Jacobson, Heléne Yorke, Billy Eichner and Paige Gilbert.

GINGER TWINSIES Company Celebrates Opening Night

Ginger Twinsies is running off-Broadway at the Orpheum Theatre.

GINGER TWINSIES Company Celebrates Opening Night

Ginger Twinsies is running off-Broadway at the Orpheum Theatre.

On the Opening Night Red Carpet for GINGER TWINSIES

Ginger Twinsies is running off-Broadway at the Orpheum Theatre.

On the Opening Night Red Carpet for GINGER TWINSIES

Ginger Twinsies is running off-Broadway at the Orpheum Theatre.

Frankie Grande Visits STRANGER THINGS: THE FIRST SHADOW

He saw the show two days in a row this week, bringing his mother Joan to the show to meet the cast as well.

Frankie Grande Visits STRANGER THINGS: THE FIRST SHADOW

He saw the show two days in a row this week, bringing his mother Joan to the show to meet the cast as well.

Review: 'JOSEPHINE' & 'PAGLIACCI' at Union Avenue Opera

runs through August 2

Review: 'JOSEPHINE' & 'PAGLIACCI' at Union Avenue Opera

runs through August 2

A PLAY ABOUT DAVID MAMET... Reading

Directed by Leslye Headland, the four-person cast featured Abbi Jacobson, Heléne Yorke, Billy Eichner and Paige Gilbert.

A PLAY ABOUT DAVID MAMET... Reading

Directed by Leslye Headland, the four-person cast featured Abbi Jacobson, Heléne Yorke, Billy Eichner and Paige Gilbert.

Broadway's Carole Demas Makes Solo Cabaret Debut in FIREFLY at 54 Below

The unforgettable show, celebrating the star's long Broadway and TV career, returns 9/6

Broadway's Carole Demas Makes Solo Cabaret Debut in FIREFLY at 54 Below

The unforgettable show, celebrating the star's long Broadway and TV career, returns 9/6

On the Opening Night Red Carpet for GINGER TWINSIES

Ginger Twinsies is running off-Broadway at the Orpheum Theatre.

On the Opening Night Red Carpet for GINGER TWINSIES

Ginger Twinsies is running off-Broadway at the Orpheum Theatre.

Frankie Grande Visits STRANGER THINGS: THE FIRST SHADOW

He saw the show two days in a row this week, bringing his mother Joan to the show to meet the cast as well.

Frankie Grande Visits STRANGER THINGS: THE FIRST SHADOW

He saw the show two days in a row this week, bringing his mother Joan to the show to meet the cast as well.

Review: 'JOSEPHINE' & 'PAGLIACCI' at Union Avenue Opera

runs through August 2

Review: 'JOSEPHINE' & 'PAGLIACCI' at Union Avenue Opera

runs through August 2

A PLAY ABOUT DAVID MAMET... Reading

Directed by Leslye Headland, the four-person cast featured Abbi Jacobson, Heléne Yorke, Billy Eichner and Paige Gilbert.

A PLAY ABOUT DAVID MAMET... Reading

Directed by Leslye Headland, the four-person cast featured Abbi Jacobson, Heléne Yorke, Billy Eichner and Paige Gilbert.

Broadway's Carole Demas Makes Solo Cabaret Debut in FIREFLY at 54 Below

The unforgettable show, celebrating the star's long Broadway and TV career, returns 9/6

Broadway's Carole Demas Makes Solo Cabaret Debut in FIREFLY at 54 Below

The unforgettable show, celebrating the star's long Broadway and TV career, returns 9/6

Lin-Manuel Miranda and Eisa Davis’s WARRIORS Silent Disco

The event began with a cocktail party in LCT3’s Claire Tow Theater followed by the dance party out on The Dance Floor at Josie Robertson Plaza.

Lin-Manuel Miranda and Eisa Davis’s WARRIORS Silent Disco

The event began with a cocktail party in LCT3’s Claire Tow Theater followed by the dance party out on The Dance Floor at Josie Robertson Plaza.

Frankie Grande Visits STRANGER THINGS: THE FIRST SHADOW

He saw the show two days in a row this week, bringing his mother Joan to the show to meet the cast as well.

Frankie Grande Visits STRANGER THINGS: THE FIRST SHADOW

He saw the show two days in a row this week, bringing his mother Joan to the show to meet the cast as well.

Review: 'JOSEPHINE' & 'PAGLIACCI' at Union Avenue Opera

runs through August 2

Review: 'JOSEPHINE' & 'PAGLIACCI' at Union Avenue Opera

runs through August 2

A PLAY ABOUT DAVID MAMET... Reading

Directed by Leslye Headland, the four-person cast featured Abbi Jacobson, Heléne Yorke, Billy Eichner and Paige Gilbert.

A PLAY ABOUT DAVID MAMET... Reading

Directed by Leslye Headland, the four-person cast featured Abbi Jacobson, Heléne Yorke, Billy Eichner and Paige Gilbert.

Broadway's Carole Demas Makes Solo Cabaret Debut in FIREFLY at 54 Below

The unforgettable show, celebrating the star's long Broadway and TV career, returns 9/6

Broadway's Carole Demas Makes Solo Cabaret Debut in FIREFLY at 54 Below

The unforgettable show, celebrating the star's long Broadway and TV career, returns 9/6

Lin-Manuel Miranda and Eisa Davis’s WARRIORS Silent Disco

The event began with a cocktail party in LCT3’s Claire Tow Theater followed by the dance party out on The Dance Floor at Josie Robertson Plaza.

Lin-Manuel Miranda and Eisa Davis’s WARRIORS Silent Disco

The event began with a cocktail party in LCT3’s Claire Tow Theater followed by the dance party out on The Dance Floor at Josie Robertson Plaza.

Teyana Taylor & Aaron Pierre Visit CHICAGO on Broadway

Chicago is currently running on Broadway at the Ambassador Theatre.

Teyana Taylor & Aaron Pierre Visit CHICAGO on Broadway

Chicago is currently running on Broadway at the Ambassador Theatre.

Review: 'JOSEPHINE' & 'PAGLIACCI' at Union Avenue Opera

runs through August 2

Review: 'JOSEPHINE' & 'PAGLIACCI' at Union Avenue Opera

runs through August 2

A PLAY ABOUT DAVID MAMET... Reading

Directed by Leslye Headland, the four-person cast featured Abbi Jacobson, Heléne Yorke, Billy Eichner and Paige Gilbert.

A PLAY ABOUT DAVID MAMET... Reading

Directed by Leslye Headland, the four-person cast featured Abbi Jacobson, Heléne Yorke, Billy Eichner and Paige Gilbert.

Broadway's Carole Demas Makes Solo Cabaret Debut in FIREFLY at 54 Below

The unforgettable show, celebrating the star's long Broadway and TV career, returns 9/6

Broadway's Carole Demas Makes Solo Cabaret Debut in FIREFLY at 54 Below

The unforgettable show, celebrating the star's long Broadway and TV career, returns 9/6

Lin-Manuel Miranda and Eisa Davis’s WARRIORS Silent Disco

The event began with a cocktail party in LCT3’s Claire Tow Theater followed by the dance party out on The Dance Floor at Josie Robertson Plaza.

Lin-Manuel Miranda and Eisa Davis’s WARRIORS Silent Disco

The event began with a cocktail party in LCT3’s Claire Tow Theater followed by the dance party out on The Dance Floor at Josie Robertson Plaza.

Teyana Taylor & Aaron Pierre Visit CHICAGO on Broadway

Chicago is currently running on Broadway at the Ambassador Theatre.

Teyana Taylor & Aaron Pierre Visit CHICAGO on Broadway

Chicago is currently running on Broadway at the Ambassador Theatre.

HAMILTON Cast Joins Talkback at Hudson Yards

Events are all free and open to the public.

HAMILTON Cast Joins Talkback at Hudson Yards

Events are all free and open to the public.

A PLAY ABOUT DAVID MAMET... Reading

Directed by Leslye Headland, the four-person cast featured Abbi Jacobson, Heléne Yorke, Billy Eichner and Paige Gilbert.

A PLAY ABOUT DAVID MAMET... Reading

Directed by Leslye Headland, the four-person cast featured Abbi Jacobson, Heléne Yorke, Billy Eichner and Paige Gilbert.

Broadway's Carole Demas Makes Solo Cabaret Debut in FIREFLY at 54 Below

The unforgettable show, celebrating the star's long Broadway and TV career, returns 9/6

Broadway's Carole Demas Makes Solo Cabaret Debut in FIREFLY at 54 Below

The unforgettable show, celebrating the star's long Broadway and TV career, returns 9/6

Lin-Manuel Miranda and Eisa Davis’s WARRIORS Silent Disco

The event began with a cocktail party in LCT3’s Claire Tow Theater followed by the dance party out on The Dance Floor at Josie Robertson Plaza.

Lin-Manuel Miranda and Eisa Davis’s WARRIORS Silent Disco

The event began with a cocktail party in LCT3’s Claire Tow Theater followed by the dance party out on The Dance Floor at Josie Robertson Plaza.

Teyana Taylor & Aaron Pierre Visit CHICAGO on Broadway

Chicago is currently running on Broadway at the Ambassador Theatre.

Teyana Taylor & Aaron Pierre Visit CHICAGO on Broadway

Chicago is currently running on Broadway at the Ambassador Theatre.

HAMILTON Cast Joins Talkback at Hudson Yards

Events are all free and open to the public.

HAMILTON Cast Joins Talkback at Hudson Yards

Events are all free and open to the public.

THE HEIDI CHRONICLES at The Group Rep

THE HEIDI CHRONICLES runs July 25 – August 31, 2025.

THE HEIDI CHRONICLES at The Group Rep

THE HEIDI CHRONICLES runs July 25 – August 31, 2025.

Broadway's Carole Demas Makes Solo Cabaret Debut in FIREFLY at 54 Below

The unforgettable show, celebrating the star's long Broadway and TV career, returns 9/6

Broadway's Carole Demas Makes Solo Cabaret Debut in FIREFLY at 54 Below

The unforgettable show, celebrating the star's long Broadway and TV career, returns 9/6

Lin-Manuel Miranda and Eisa Davis’s WARRIORS Silent Disco

The event began with a cocktail party in LCT3’s Claire Tow Theater followed by the dance party out on The Dance Floor at Josie Robertson Plaza.

Lin-Manuel Miranda and Eisa Davis’s WARRIORS Silent Disco

The event began with a cocktail party in LCT3’s Claire Tow Theater followed by the dance party out on The Dance Floor at Josie Robertson Plaza.

Teyana Taylor & Aaron Pierre Visit CHICAGO on Broadway

Chicago is currently running on Broadway at the Ambassador Theatre.

Teyana Taylor & Aaron Pierre Visit CHICAGO on Broadway

Chicago is currently running on Broadway at the Ambassador Theatre.

HAMILTON Cast Joins Talkback at Hudson Yards

Events are all free and open to the public.

HAMILTON Cast Joins Talkback at Hudson Yards

Events are all free and open to the public.

THE HEIDI CHRONICLES at The Group Rep

THE HEIDI CHRONICLES runs July 25 – August 31, 2025.

THE HEIDI CHRONICLES at The Group Rep

THE HEIDI CHRONICLES runs July 25 – August 31, 2025.

Ryan O’Connor-Helmed MENAGE A QUATRE at the Davidson/Valentini Theatre

MÉNAGE À QUATRE will perform through Sunday, August 17 at the Davidson/Valentini Theatre at the Los Angeles LGBT Center.

Ryan O’Connor-Helmed MENAGE A QUATRE at the Davidson/Valentini Theatre

MÉNAGE À QUATRE will perform through Sunday, August 17 at the Davidson/Valentini Theatre at the Los Angeles LGBT Center.

Lin-Manuel Miranda and Eisa Davis’s WARRIORS Silent Disco

The event began with a cocktail party in LCT3’s Claire Tow Theater followed by the dance party out on The Dance Floor at Josie Robertson Plaza.

Lin-Manuel Miranda and Eisa Davis’s WARRIORS Silent Disco

The event began with a cocktail party in LCT3’s Claire Tow Theater followed by the dance party out on The Dance Floor at Josie Robertson Plaza.

Teyana Taylor & Aaron Pierre Visit CHICAGO on Broadway

Chicago is currently running on Broadway at the Ambassador Theatre.

Teyana Taylor & Aaron Pierre Visit CHICAGO on Broadway

Chicago is currently running on Broadway at the Ambassador Theatre.

HAMILTON Cast Joins Talkback at Hudson Yards

Events are all free and open to the public.

HAMILTON Cast Joins Talkback at Hudson Yards

Events are all free and open to the public.

THE HEIDI CHRONICLES at The Group Rep

THE HEIDI CHRONICLES runs July 25 – August 31, 2025.

THE HEIDI CHRONICLES at The Group Rep

THE HEIDI CHRONICLES runs July 25 – August 31, 2025.

Ryan O’Connor-Helmed MENAGE A QUATRE at the Davidson/Valentini Theatre

MÉNAGE À QUATRE will perform through Sunday, August 17 at the Davidson/Valentini Theatre at the Los Angeles LGBT Center.

Ryan O’Connor-Helmed MENAGE A QUATRE at the Davidson/Valentini Theatre

MÉNAGE À QUATRE will perform through Sunday, August 17 at the Davidson/Valentini Theatre at the Los Angeles LGBT Center.

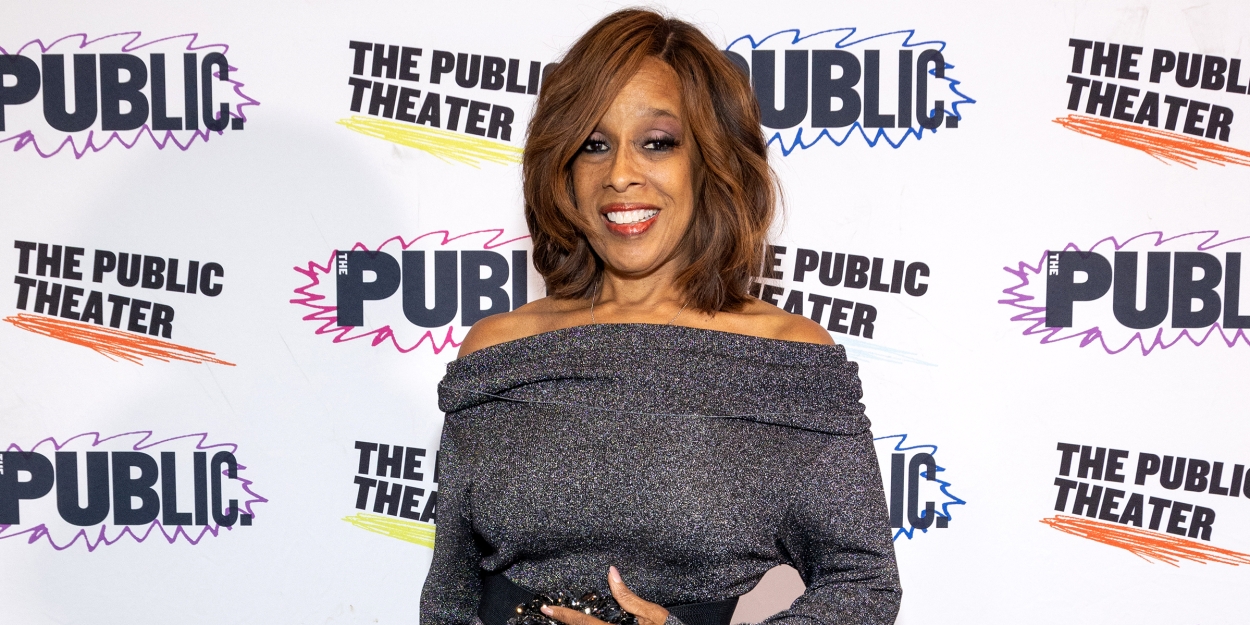

Hoda Kotb Visits JOY: A NEW TRUE MUSICAL

Joy is running off-Broadway at the Laura Pels Theatre.

Hoda Kotb Visits JOY: A NEW TRUE MUSICAL

Joy is running off-Broadway at the Laura Pels Theatre.

Teyana Taylor & Aaron Pierre Visit CHICAGO on Broadway

Chicago is currently running on Broadway at the Ambassador Theatre.

Teyana Taylor & Aaron Pierre Visit CHICAGO on Broadway

Chicago is currently running on Broadway at the Ambassador Theatre.

HAMILTON Cast Joins Talkback at Hudson Yards

Events are all free and open to the public.

HAMILTON Cast Joins Talkback at Hudson Yards

Events are all free and open to the public.

THE HEIDI CHRONICLES at The Group Rep

THE HEIDI CHRONICLES runs July 25 – August 31, 2025.

THE HEIDI CHRONICLES at The Group Rep

THE HEIDI CHRONICLES runs July 25 – August 31, 2025.

Ryan O’Connor-Helmed MENAGE A QUATRE at the Davidson/Valentini Theatre

MÉNAGE À QUATRE will perform through Sunday, August 17 at the Davidson/Valentini Theatre at the Los Angeles LGBT Center.

Ryan O’Connor-Helmed MENAGE A QUATRE at the Davidson/Valentini Theatre

MÉNAGE À QUATRE will perform through Sunday, August 17 at the Davidson/Valentini Theatre at the Los Angeles LGBT Center.

Hoda Kotb Visits JOY: A NEW TRUE MUSICAL

Joy is running off-Broadway at the Laura Pels Theatre.

Hoda Kotb Visits JOY: A NEW TRUE MUSICAL

Joy is running off-Broadway at the Laura Pels Theatre.

Inside A CHORUS LINE's 50th Anniversary Celebration

The event featured original stars Baayork Lee, Kelly Bishop, Wayne Cilento,

Inside A CHORUS LINE's 50th Anniversary Celebration

The event featured original stars Baayork Lee, Kelly Bishop, Wayne Cilento,

HAMILTON Cast Joins Talkback at Hudson Yards

Events are all free and open to the public.

HAMILTON Cast Joins Talkback at Hudson Yards

Events are all free and open to the public.

THE HEIDI CHRONICLES at The Group Rep

THE HEIDI CHRONICLES runs July 25 – August 31, 2025.

THE HEIDI CHRONICLES at The Group Rep

THE HEIDI CHRONICLES runs July 25 – August 31, 2025.

Ryan O’Connor-Helmed MENAGE A QUATRE at the Davidson/Valentini Theatre

MÉNAGE À QUATRE will perform through Sunday, August 17 at the Davidson/Valentini Theatre at the Los Angeles LGBT Center.

Ryan O’Connor-Helmed MENAGE A QUATRE at the Davidson/Valentini Theatre

MÉNAGE À QUATRE will perform through Sunday, August 17 at the Davidson/Valentini Theatre at the Los Angeles LGBT Center.

Hoda Kotb Visits JOY: A NEW TRUE MUSICAL

Joy is running off-Broadway at the Laura Pels Theatre.

Hoda Kotb Visits JOY: A NEW TRUE MUSICAL

Joy is running off-Broadway at the Laura Pels Theatre.

Inside A CHORUS LINE's 50th Anniversary Celebration

The event featured original stars Baayork Lee, Kelly Bishop, Wayne Cilento,

Inside A CHORUS LINE's 50th Anniversary Celebration

The event featured original stars Baayork Lee, Kelly Bishop, Wayne Cilento,

Scherzinger and the Cast of SUNSET BLVD. Take Final Bow

The show played its final performance on July 20 at the St. James Theatre following 20 previews and 312 regular performances.

Scherzinger and the Cast of SUNSET BLVD. Take Final Bow

The show played its final performance on July 20 at the St. James Theatre following 20 previews and 312 regular performances.

THE HEIDI CHRONICLES at The Group Rep

THE HEIDI CHRONICLES runs July 25 – August 31, 2025.

THE HEIDI CHRONICLES at The Group Rep

THE HEIDI CHRONICLES runs July 25 – August 31, 2025.

Ryan O’Connor-Helmed MENAGE A QUATRE at the Davidson/Valentini Theatre

MÉNAGE À QUATRE will perform through Sunday, August 17 at the Davidson/Valentini Theatre at the Los Angeles LGBT Center.

Ryan O’Connor-Helmed MENAGE A QUATRE at the Davidson/Valentini Theatre

MÉNAGE À QUATRE will perform through Sunday, August 17 at the Davidson/Valentini Theatre at the Los Angeles LGBT Center.

Hoda Kotb Visits JOY: A NEW TRUE MUSICAL

Joy is running off-Broadway at the Laura Pels Theatre.

Hoda Kotb Visits JOY: A NEW TRUE MUSICAL

Joy is running off-Broadway at the Laura Pels Theatre.

Inside A CHORUS LINE's 50th Anniversary Celebration

The event featured original stars Baayork Lee, Kelly Bishop, Wayne Cilento,

Inside A CHORUS LINE's 50th Anniversary Celebration

The event featured original stars Baayork Lee, Kelly Bishop, Wayne Cilento,

Scherzinger and the Cast of SUNSET BLVD. Take Final Bow

The show played its final performance on July 20 at the St. James Theatre following 20 previews and 312 regular performances.

Scherzinger and the Cast of SUNSET BLVD. Take Final Bow

The show played its final performance on July 20 at the St. James Theatre following 20 previews and 312 regular performances.

Robyn Hurder, Andrew Durand, and More Star in HIGH SOCIETY at Ogunquit Playhouse

The production runs July 24 through August 23 in Ogunquit, Maine.

Robyn Hurder, Andrew Durand, and More Star in HIGH SOCIETY at Ogunquit Playhouse

The production runs July 24 through August 23 in Ogunquit, Maine.

Ryan O’Connor-Helmed MENAGE A QUATRE at the Davidson/Valentini Theatre

MÉNAGE À QUATRE will perform through Sunday, August 17 at the Davidson/Valentini Theatre at the Los Angeles LGBT Center.

Ryan O’Connor-Helmed MENAGE A QUATRE at the Davidson/Valentini Theatre

MÉNAGE À QUATRE will perform through Sunday, August 17 at the Davidson/Valentini Theatre at the Los Angeles LGBT Center.

Hoda Kotb Visits JOY: A NEW TRUE MUSICAL

Joy is running off-Broadway at the Laura Pels Theatre.

Hoda Kotb Visits JOY: A NEW TRUE MUSICAL

Joy is running off-Broadway at the Laura Pels Theatre.

Inside A CHORUS LINE's 50th Anniversary Celebration

The event featured original stars Baayork Lee, Kelly Bishop, Wayne Cilento,

Inside A CHORUS LINE's 50th Anniversary Celebration

The event featured original stars Baayork Lee, Kelly Bishop, Wayne Cilento,

Scherzinger and the Cast of SUNSET BLVD. Take Final Bow

The show played its final performance on July 20 at the St. James Theatre following 20 previews and 312 regular performances.

Scherzinger and the Cast of SUNSET BLVD. Take Final Bow

The show played its final performance on July 20 at the St. James Theatre following 20 previews and 312 regular performances.

Robyn Hurder, Andrew Durand, and More Star in HIGH SOCIETY at Ogunquit Playhouse

The production runs July 24 through August 23 in Ogunquit, Maine.

Robyn Hurder, Andrew Durand, and More Star in HIGH SOCIETY at Ogunquit Playhouse

The production runs July 24 through August 23 in Ogunquit, Maine.

Billy Porter and Marisha Wallace in CABARET

Porter and Wallace begin performances on Tuesday, July 22.

Billy Porter and Marisha Wallace in CABARET

Porter and Wallace begin performances on Tuesday, July 22.

Hoda Kotb Visits JOY: A NEW TRUE MUSICAL

Joy is running off-Broadway at the Laura Pels Theatre.

Hoda Kotb Visits JOY: A NEW TRUE MUSICAL

Joy is running off-Broadway at the Laura Pels Theatre.

Inside A CHORUS LINE's 50th Anniversary Celebration

The event featured original stars Baayork Lee, Kelly Bishop, Wayne Cilento,

Inside A CHORUS LINE's 50th Anniversary Celebration

The event featured original stars Baayork Lee, Kelly Bishop, Wayne Cilento,

Scherzinger and the Cast of SUNSET BLVD. Take Final Bow

The show played its final performance on July 20 at the St. James Theatre following 20 previews and 312 regular performances.

Scherzinger and the Cast of SUNSET BLVD. Take Final Bow

The show played its final performance on July 20 at the St. James Theatre following 20 previews and 312 regular performances.

Robyn Hurder, Andrew Durand, and More Star in HIGH SOCIETY at Ogunquit Playhouse

The production runs July 24 through August 23 in Ogunquit, Maine.

Robyn Hurder, Andrew Durand, and More Star in HIGH SOCIETY at Ogunquit Playhouse

The production runs July 24 through August 23 in Ogunquit, Maine.

Billy Porter and Marisha Wallace in CABARET

Porter and Wallace begin performances on Tuesday, July 22.

Billy Porter and Marisha Wallace in CABARET

Porter and Wallace begin performances on Tuesday, July 22.

Jess Folley, Todrick Hall and More in BURLESQUE THE MUSICAL in London

The show plays for a limited season until Saturday 6 September 2025.

Jess Folley, Todrick Hall and More in BURLESQUE THE MUSICAL in London

The show plays for a limited season until Saturday 6 September 2025.

Industry

Get Broadway's #1 Newsletter

West End

Review: CLIVE, Arcola Theatre

Didn’t we all go a little insane during the pandemic?

Didn’t we all go a little insane during the pandemic?

New York City

Interview: ZaZa Flamenca on International Cabaret CHANSONS ET TANGO at Pangea

The international duo ZaZa Flamenca and Gabriel Hermida will “set off a fireworks display of romantic songs from France and Argentina” on 8/21 and 8/28

The international duo ZaZa Flamenca and Gabriel Hermida will “set off a fireworks display of romantic songs from France and Argentina” on 8/21 and 8/28

United States

Feature: PIPPIN at The Off-Beat Players

Pippin will run through August 2 at 7:30 at the Performing Arts Center of Greenwich Country Day School.

Pippin will run through August 2 at 7:30 at the Performing Arts Center of Greenwich Country Day School.

International

EDINBURGH 2025: Review: ROSIE O'DONNELL: COMMON KNOWLEDGE, Gilded Balloon

Rosie O'Donnell: Common Knowledge runs at Edfringe until 10 August

Rosie O'Donnell: Common Knowledge runs at Edfringe until 10 August